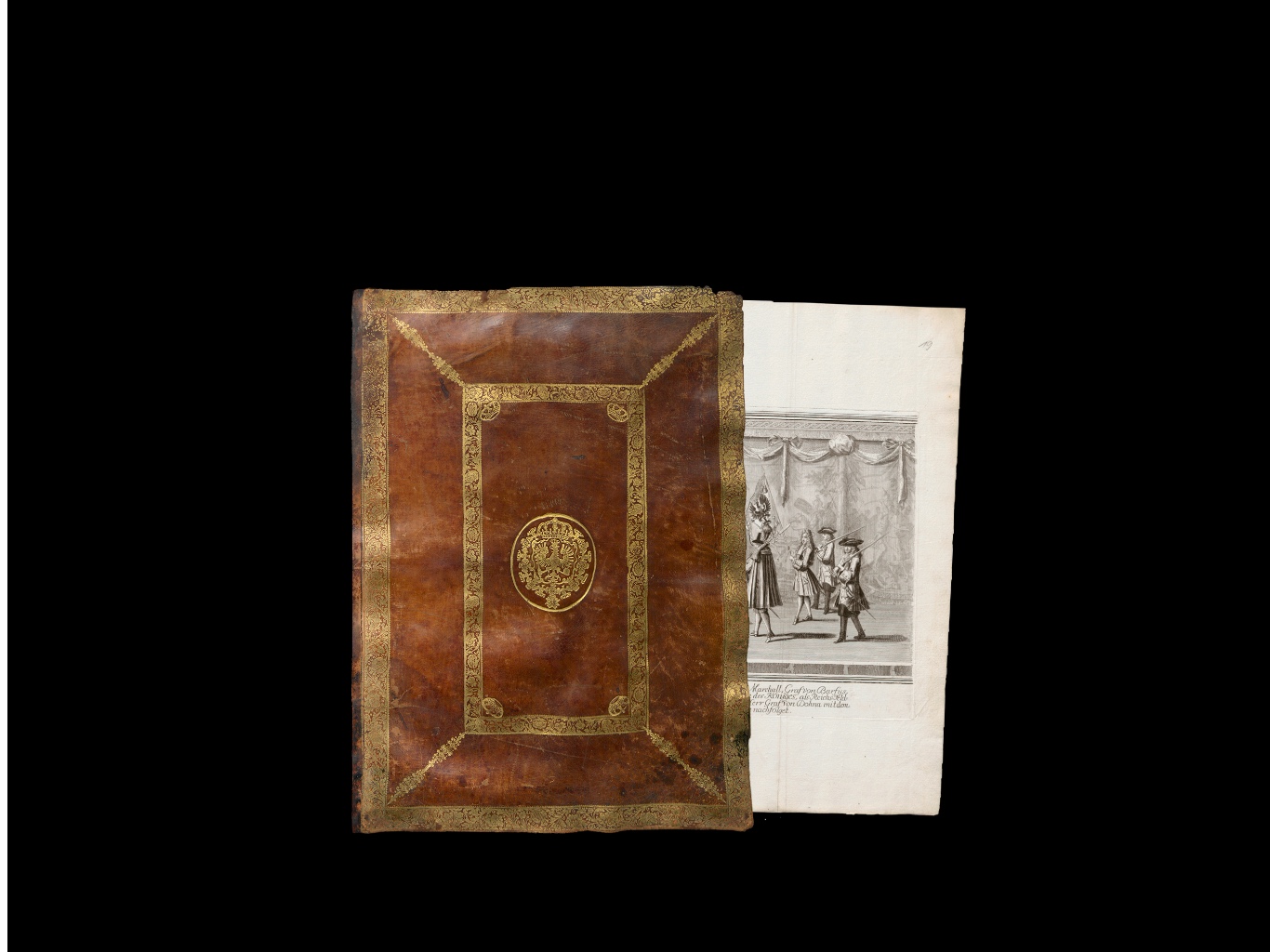

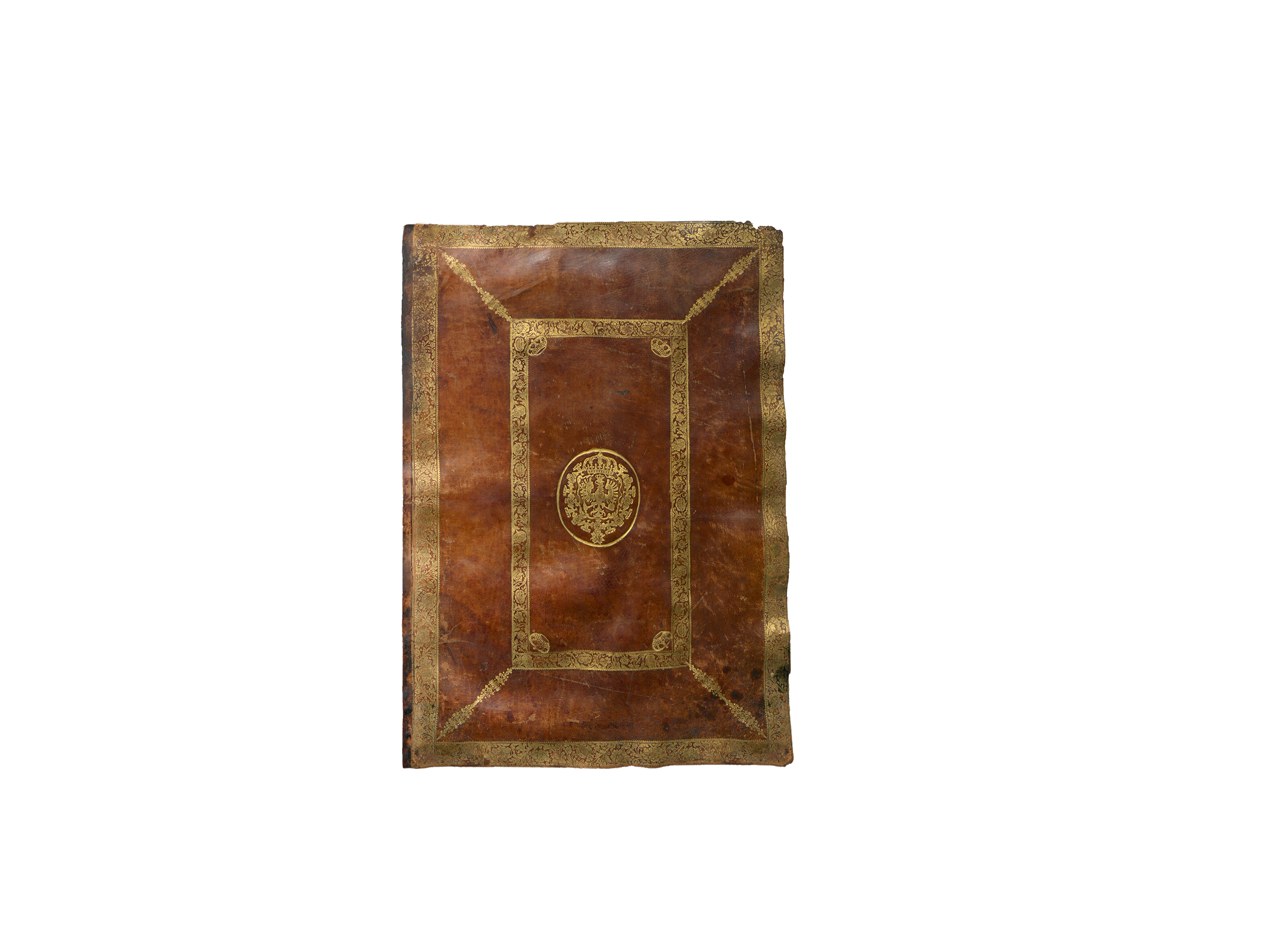

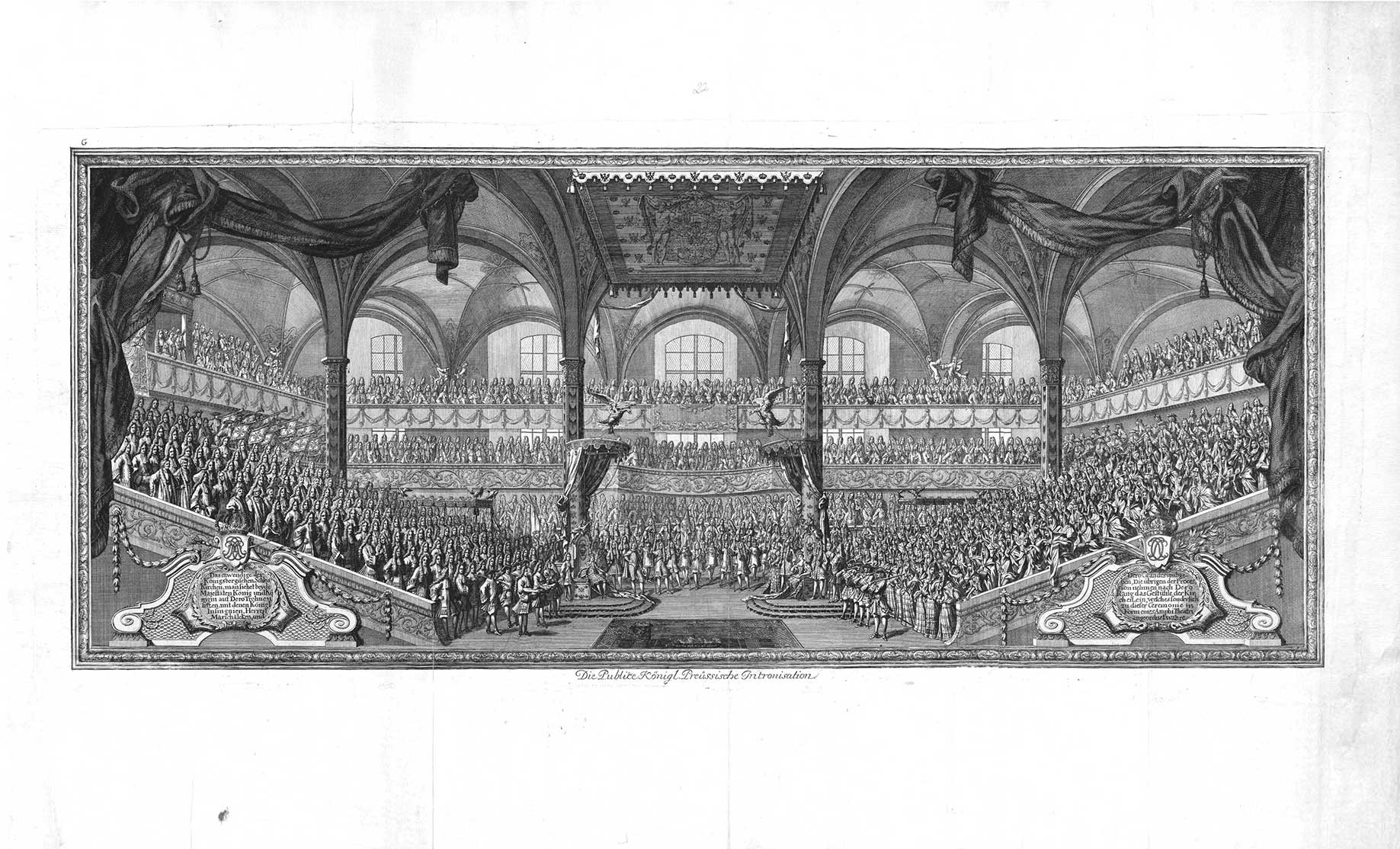

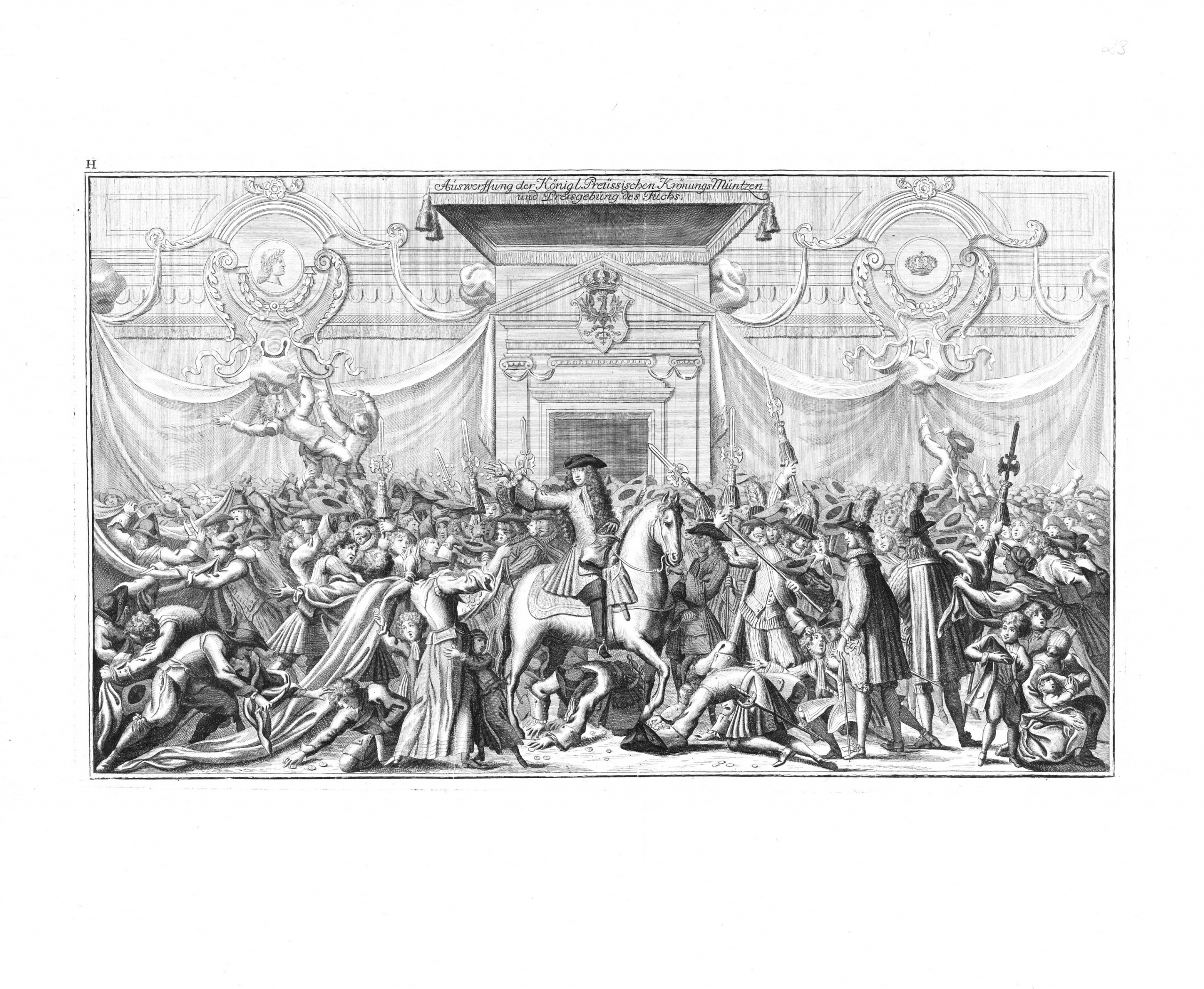

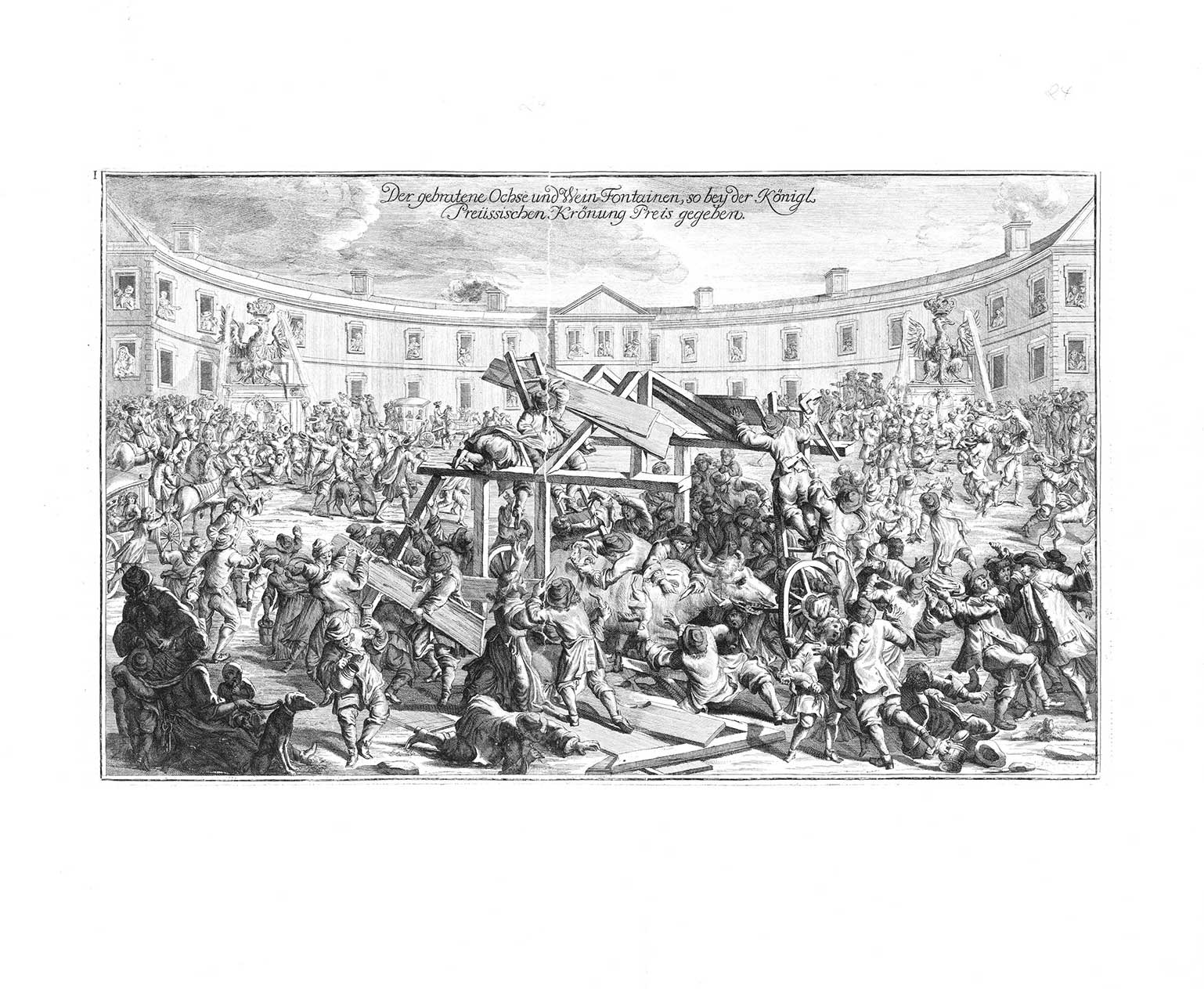

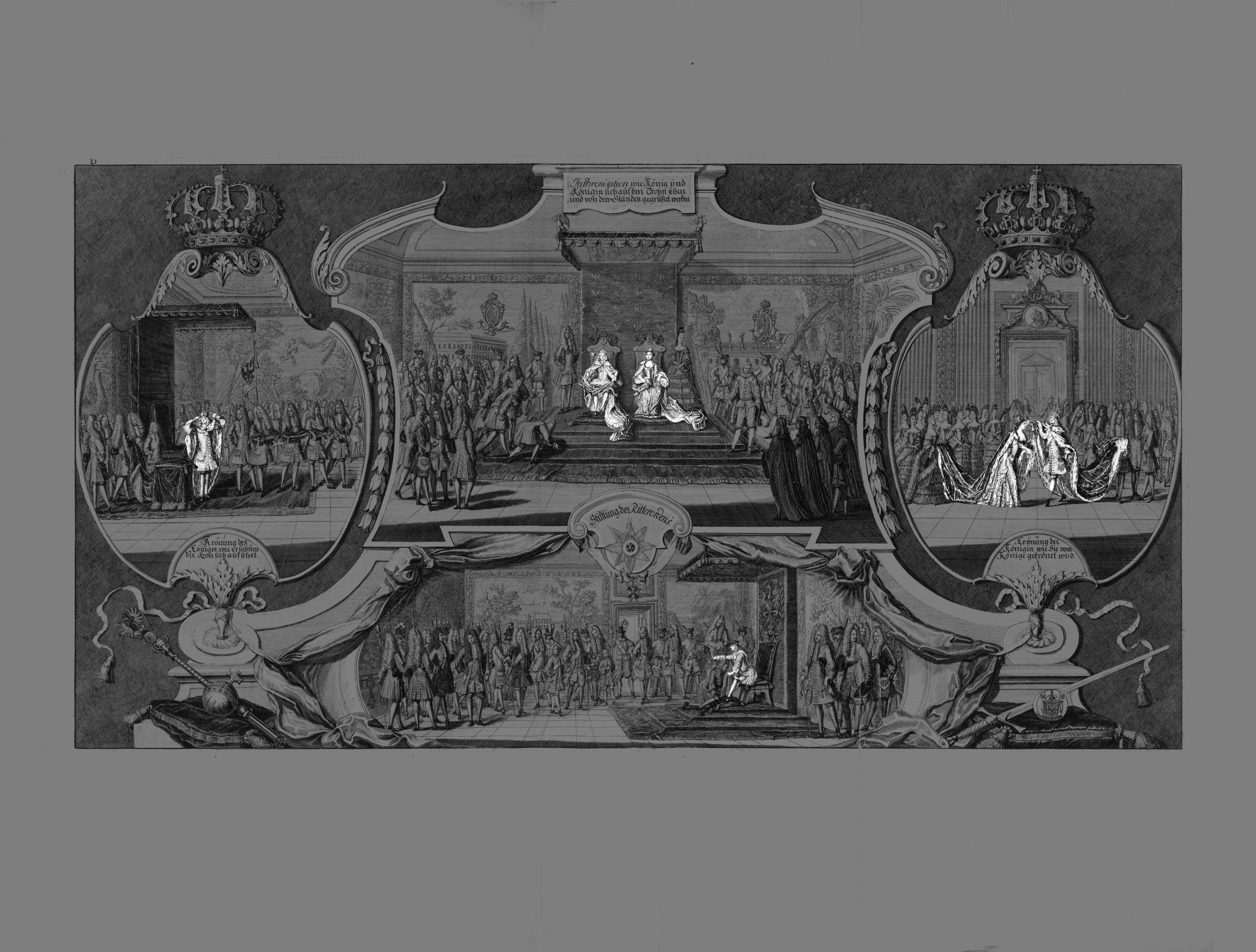

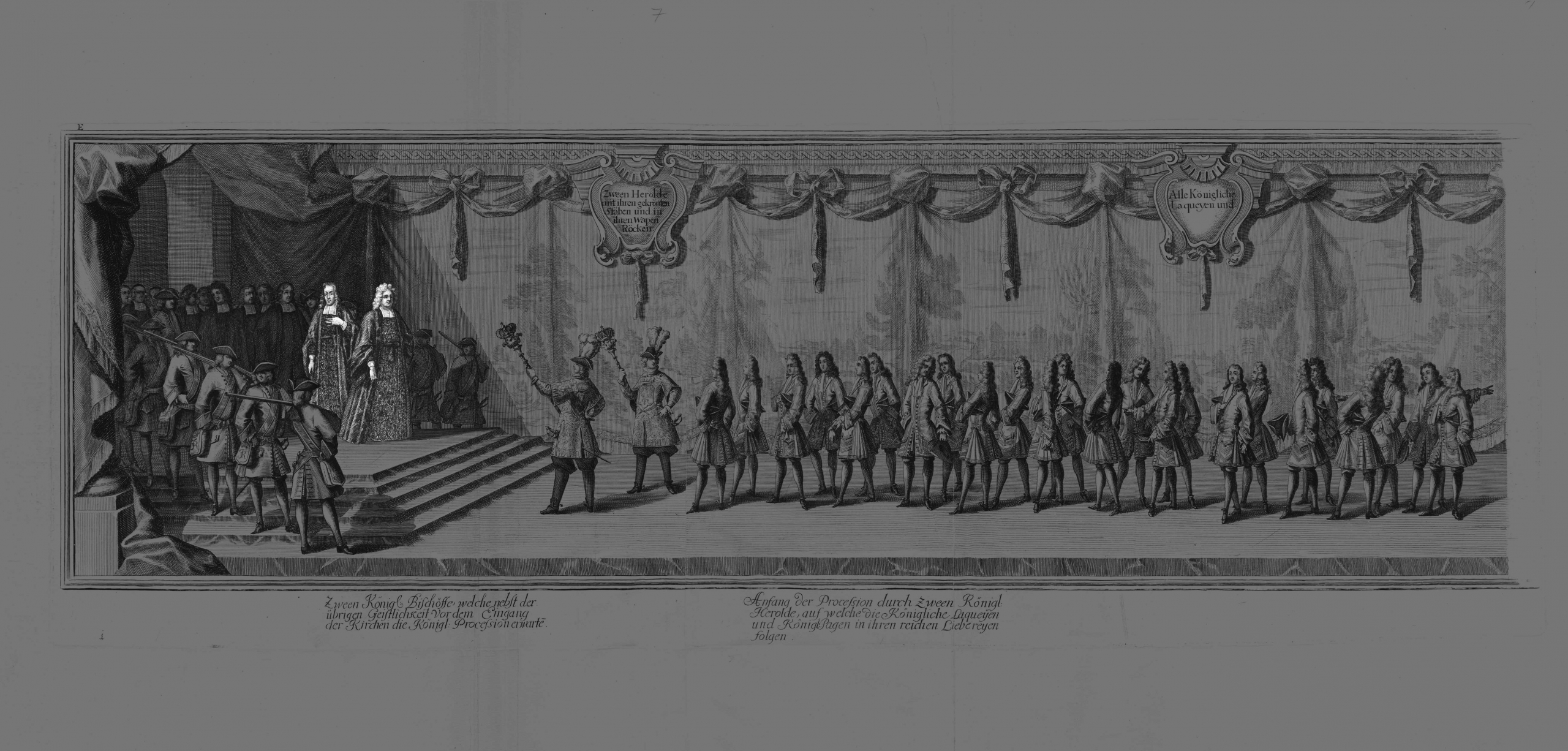

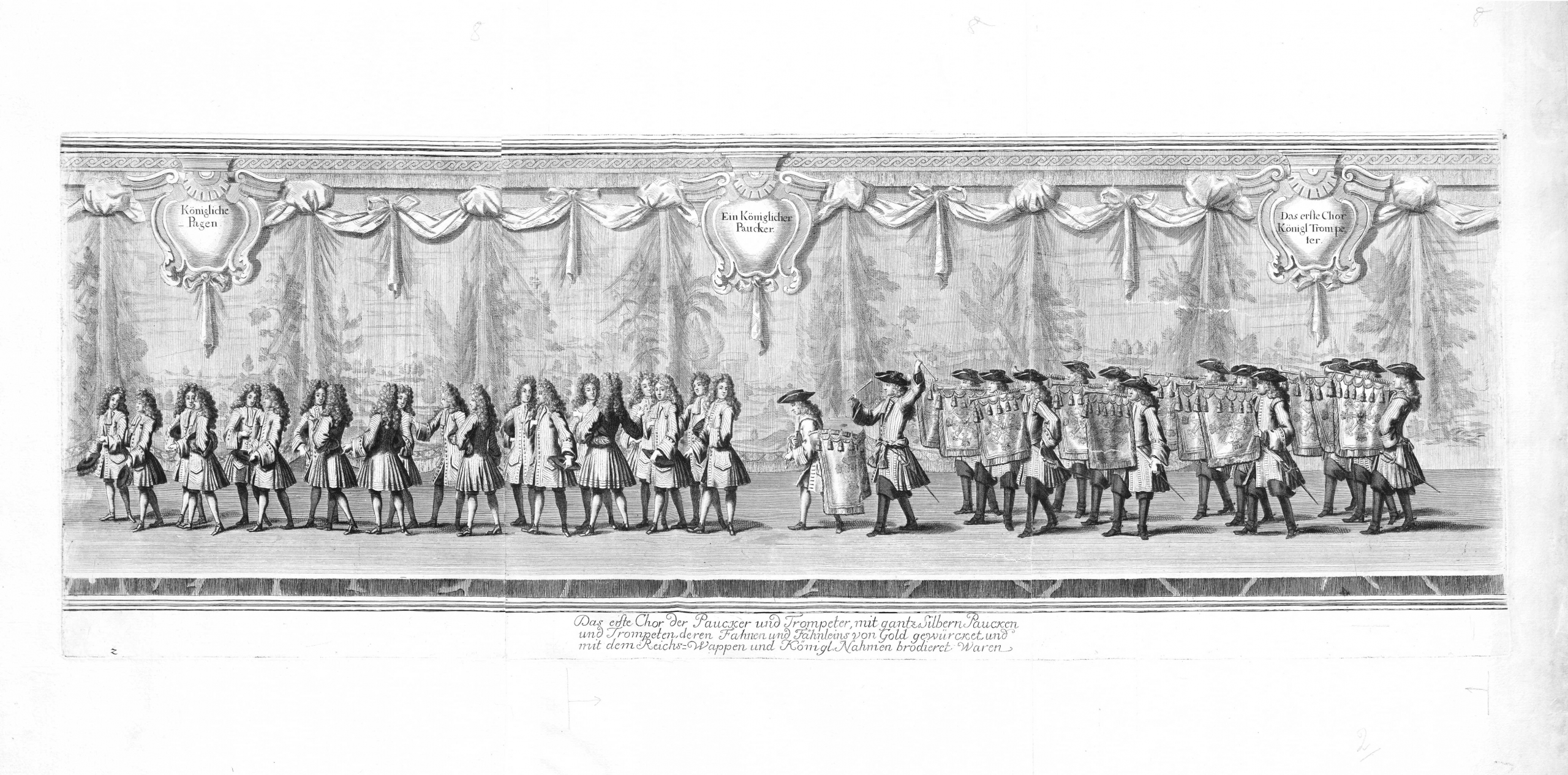

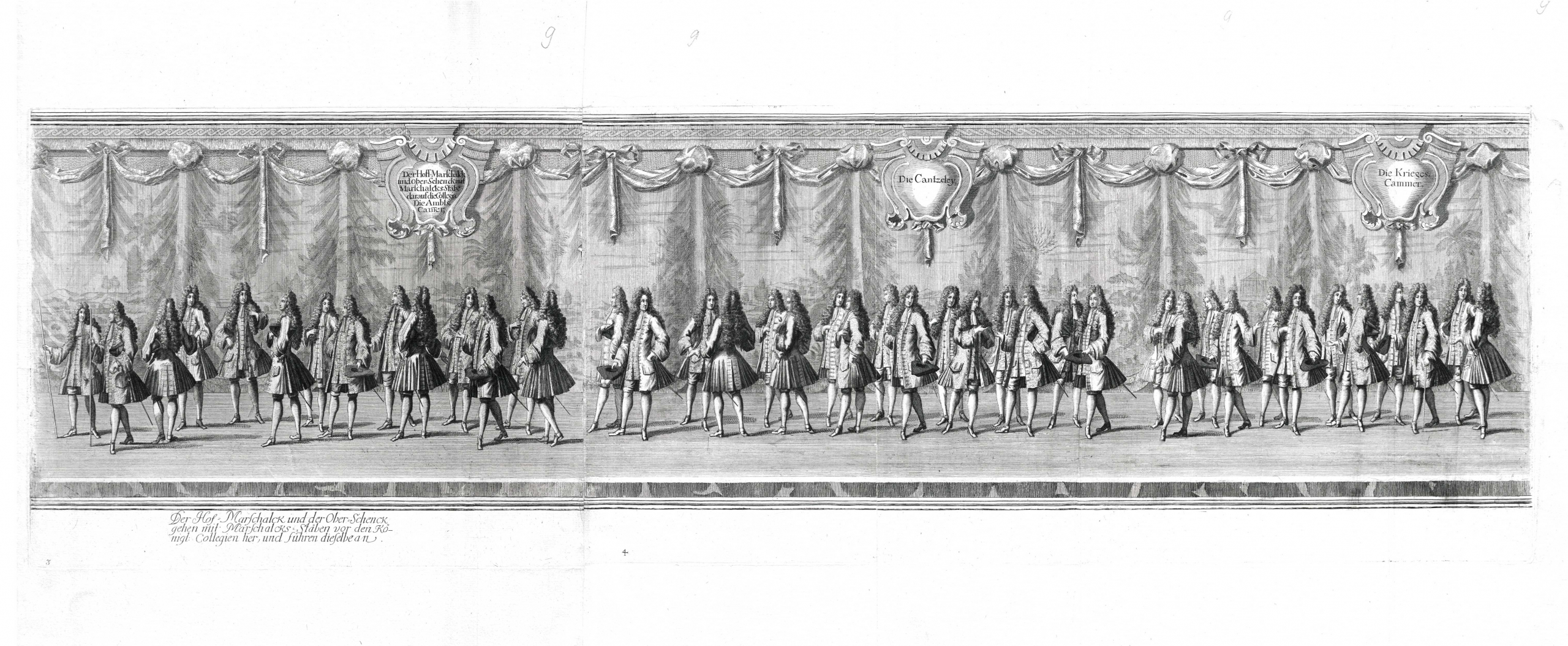

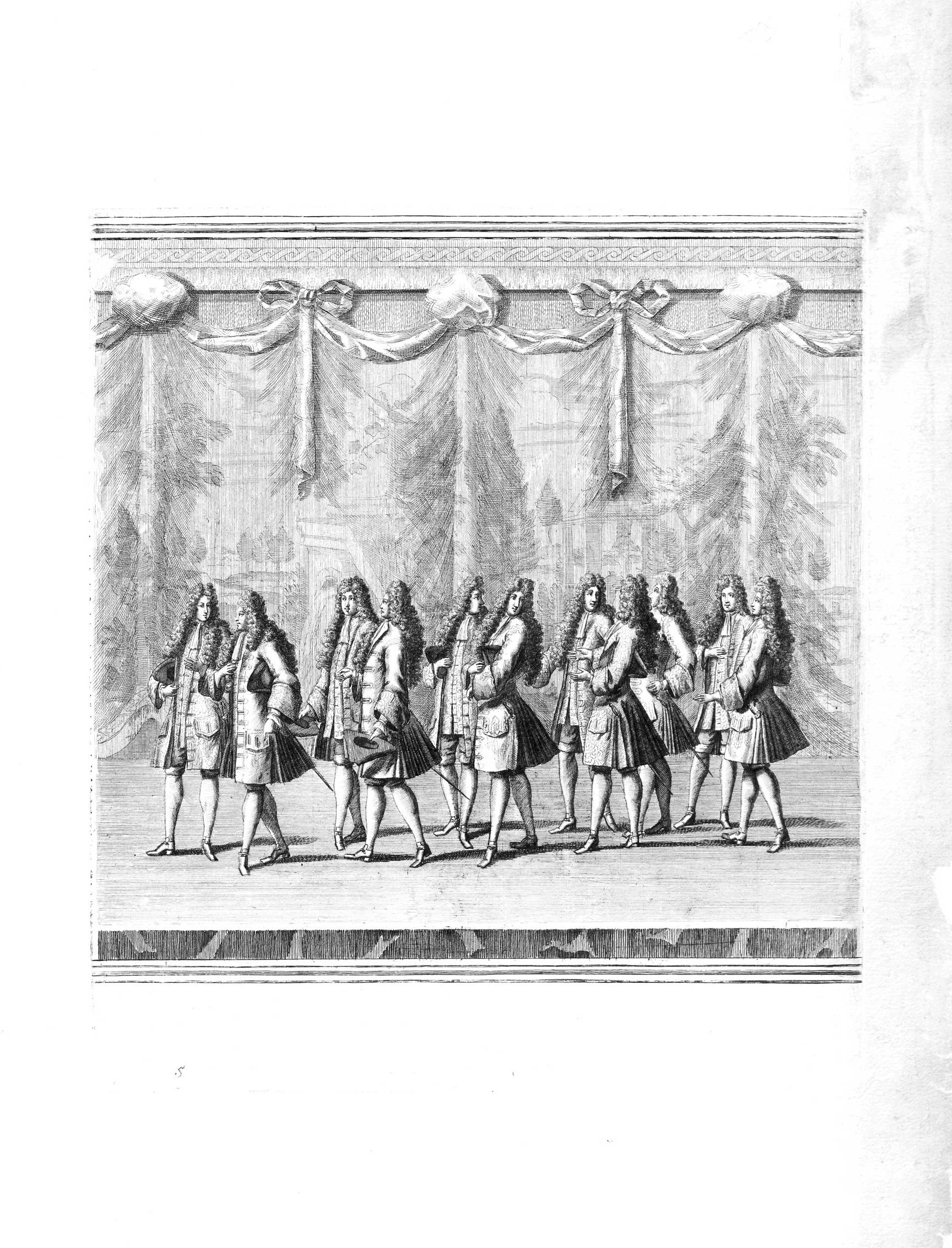

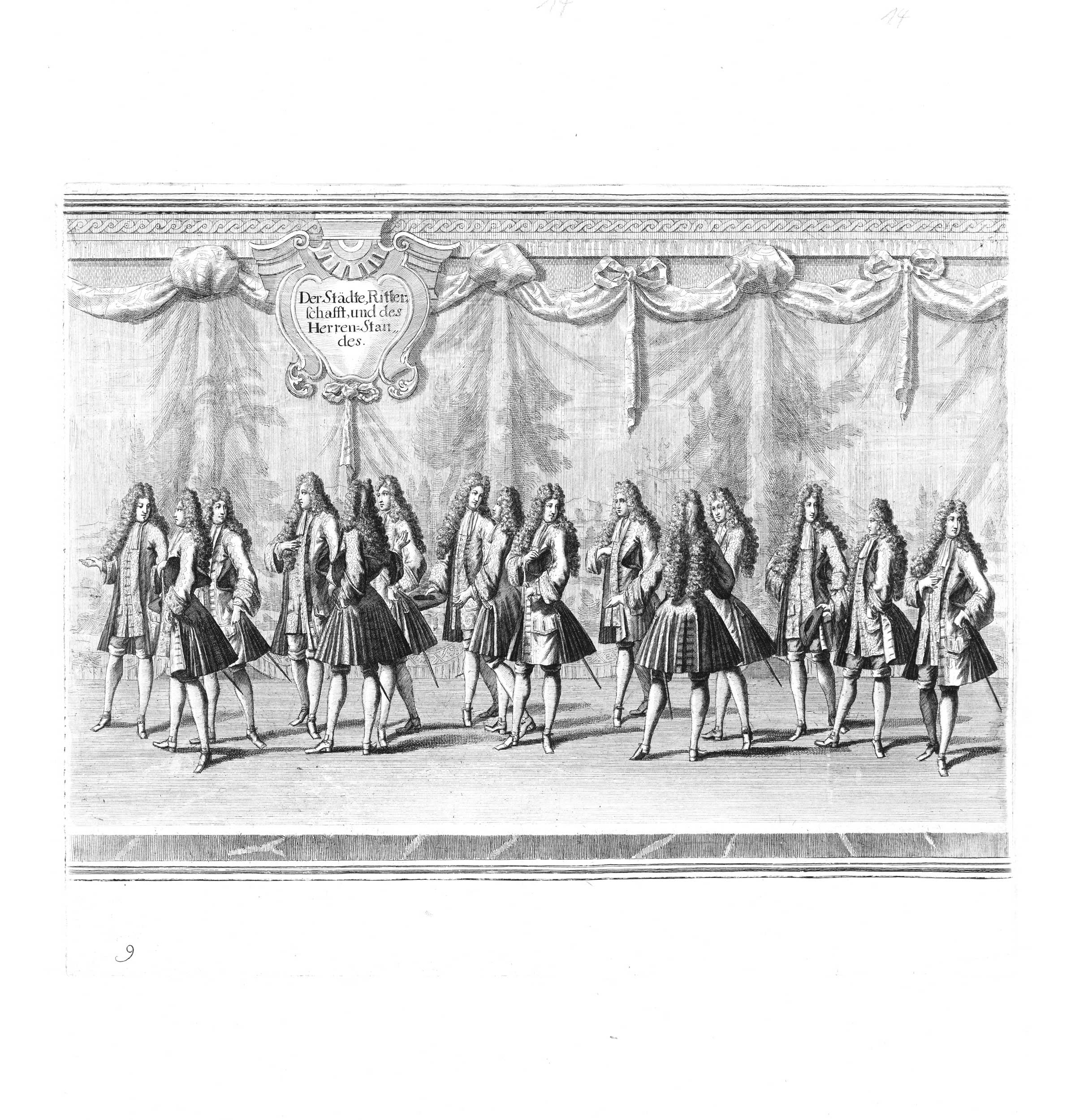

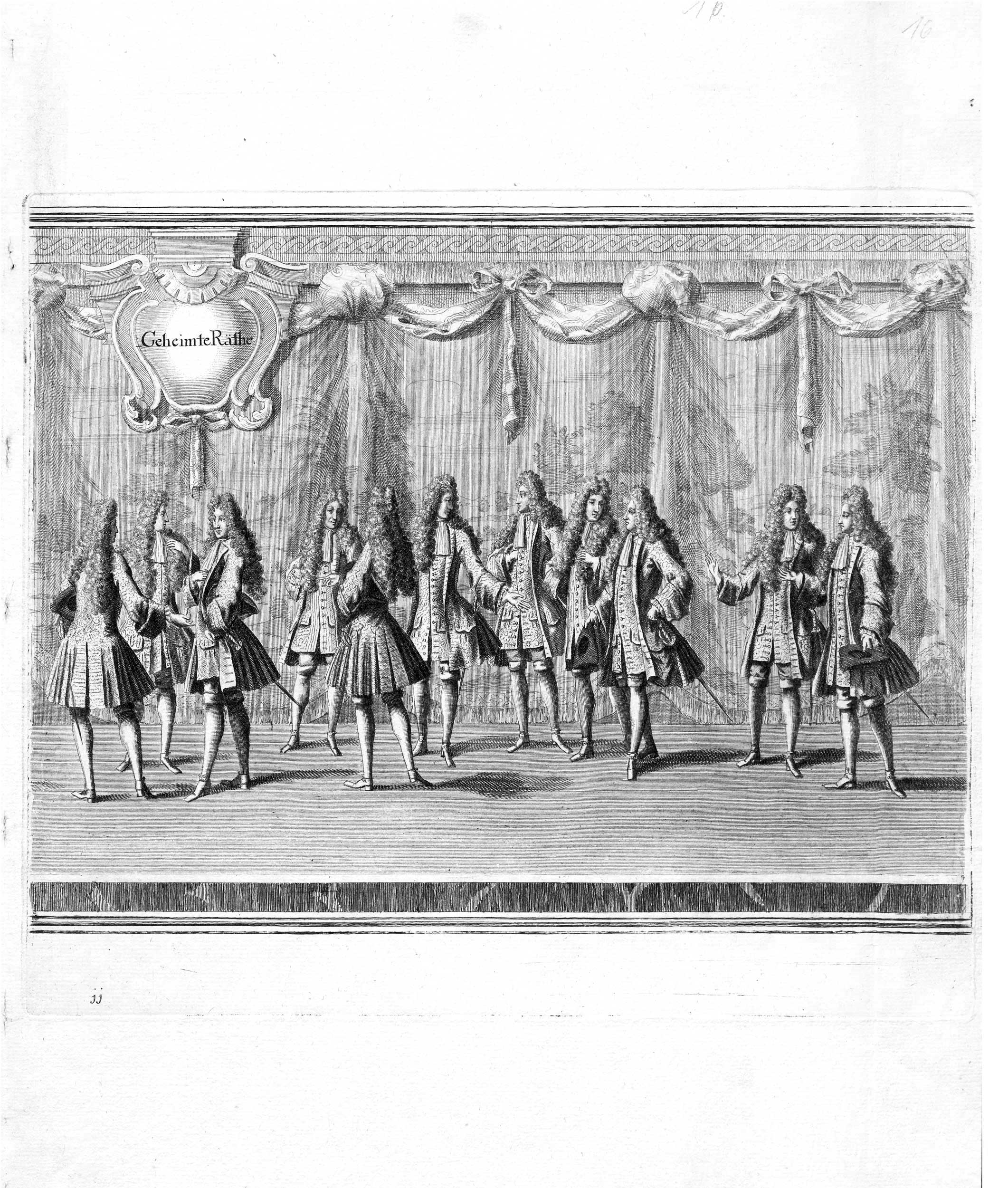

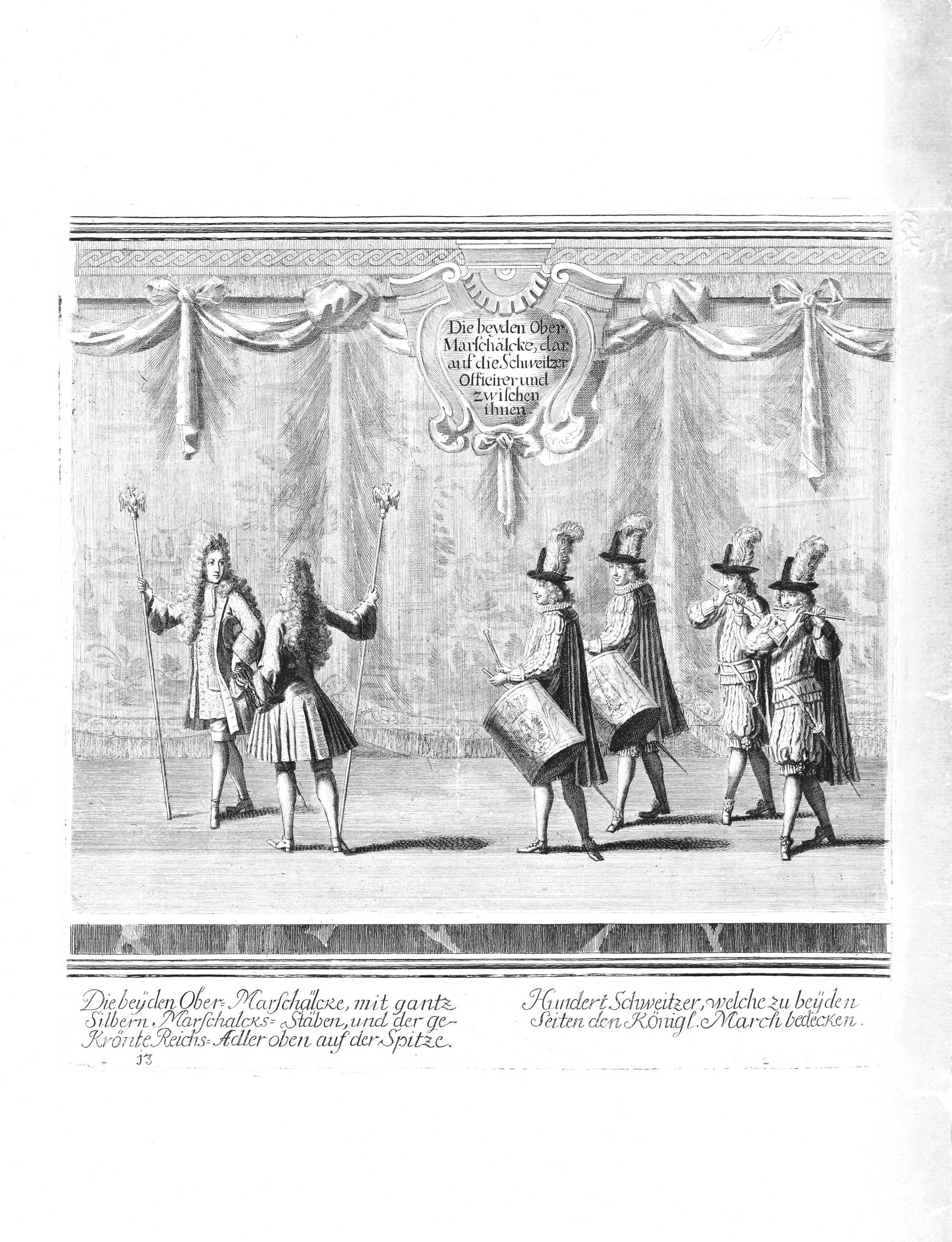

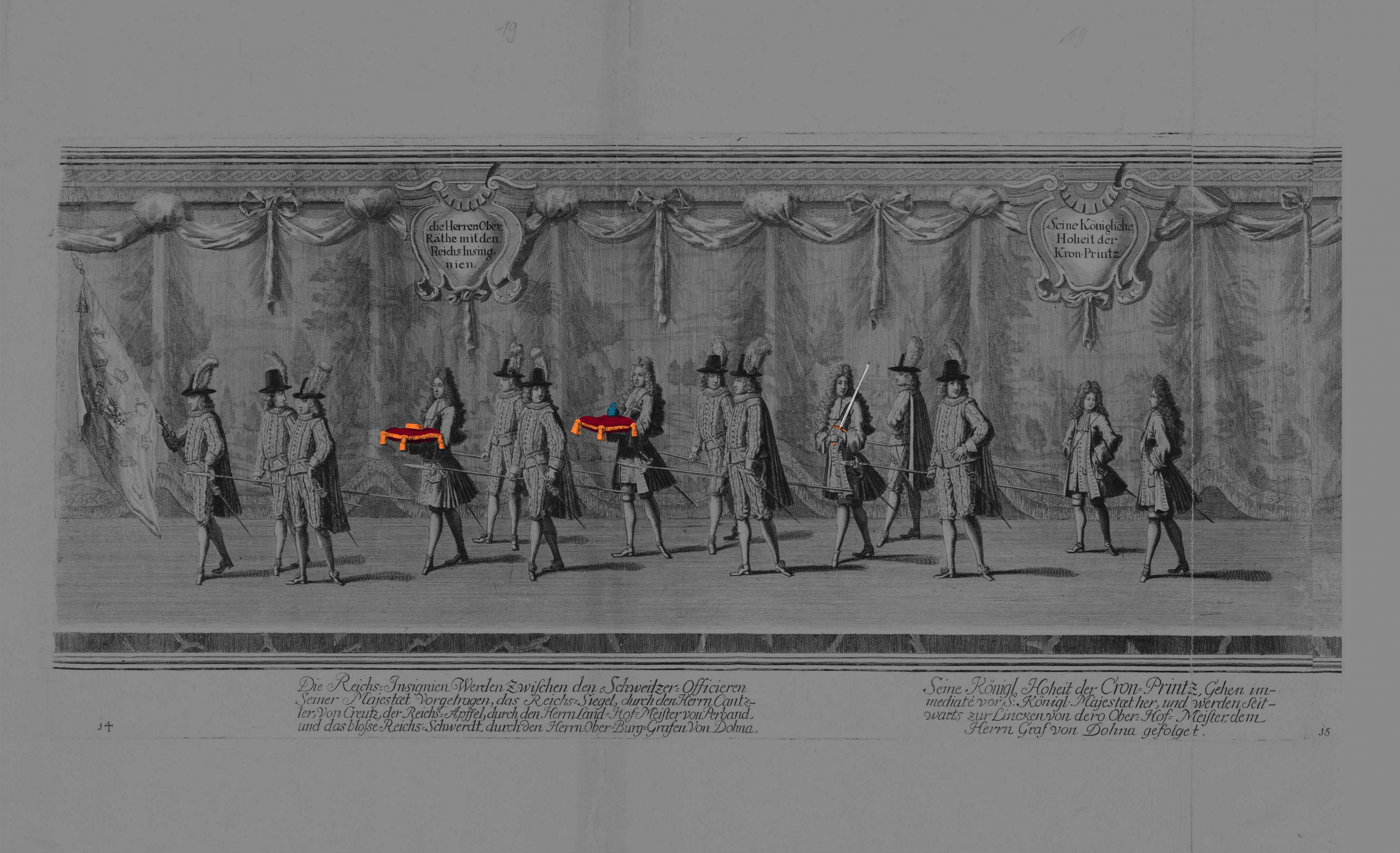

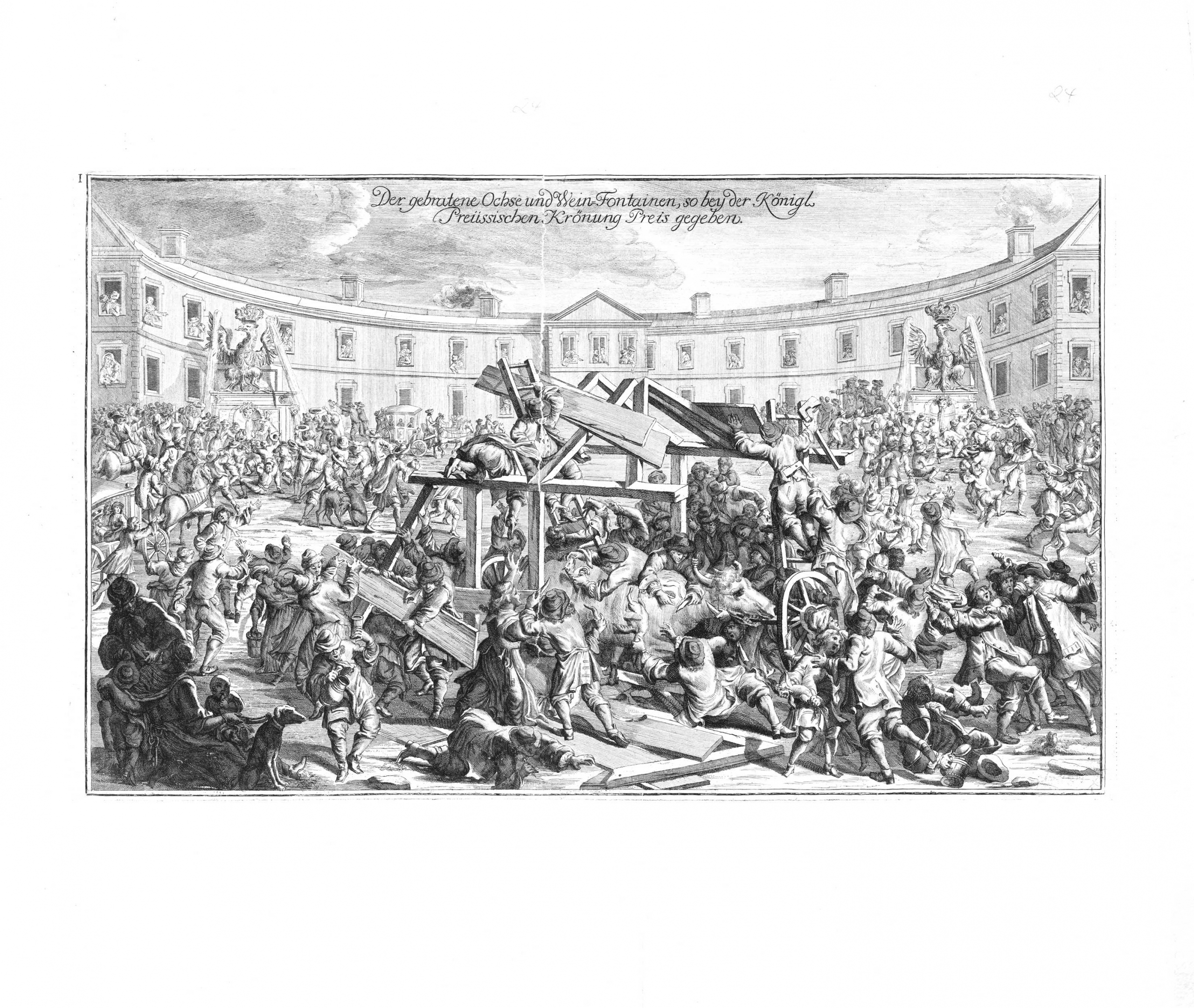

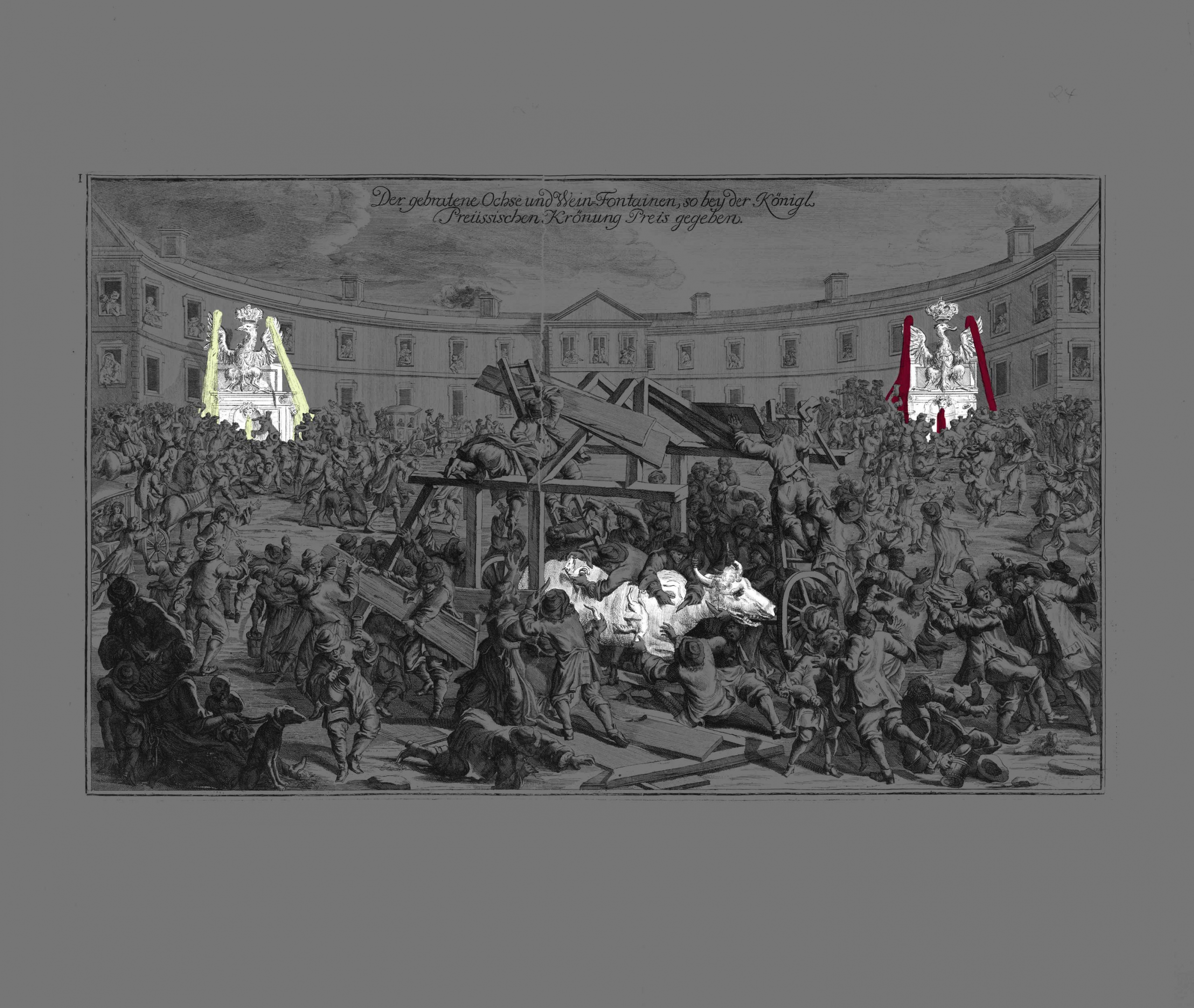

Over 20 copperplate engravings illustrate a ceremonial act

The first Prussian coronation in the year 1701

The Prussian crown was not built on inheritance, war, election, or elevated status. It was an official agreement made during diplomatic negotiations with the Holy Roman Emperor. Even though the political circumstances to create a new monarchy were favourable, the coronation did not receive as much attention as desired.

The copperplate engravings of the coronation were to counteract this. They were published alongside the report The History of the Prussian Coronation by the head of ceremonial proceedings, Johann von Besser. This account of the event permanently recorded the coronation ceremony and helped consolidate royal power. The detailed commentary by Besser is particularly useful in understanding how and why certain decisions about the ceremony were made. The combination of imagery and text is the most important source in recreating the coronation ceremony of the first Prussian King even though this cannot be regarded as a factual report.

Nothing was left to chance at the coronation of Friedrich I – and not in the production of the copperplate engravings either. The ceremonials and protocol were key elements of everyday court life during the time of Absolutism around 1700. Therefore, the ceremonial procedure of the coronation was meticulously orchestrated by Friedrich and his advisors and reveals how the Prussian King saw himself.

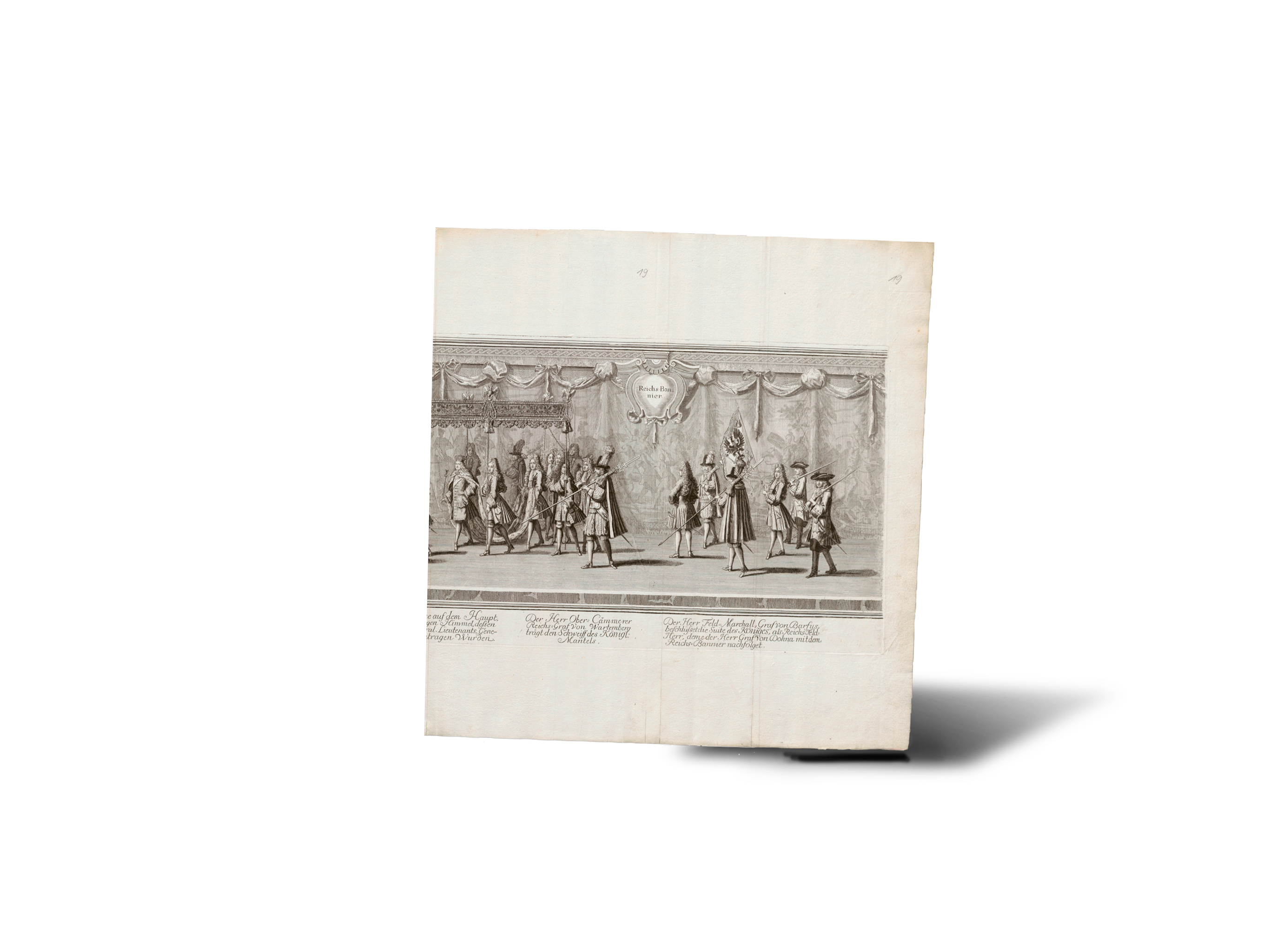

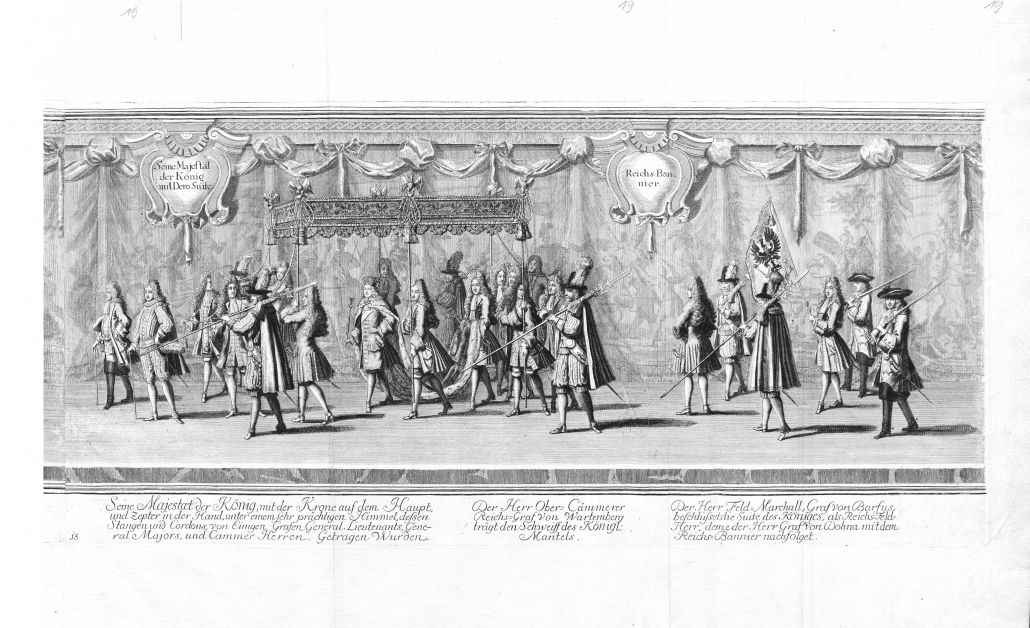

Detail from the coronation procession: The King on his way to the Schlosskirche. SBB-PK. Public Domain Mark 1.0

Portrait of Friedrich I. SBB-PK. Public Domain Mark 1.0

Origin and production

Johann von Besser’s report on Friedrich I’s coronation was first printed in 1702, one year after the event had taken place. The second edition, which included the copperplate engravings, was not published until 1712. The number and large scale of the copperplate engravings increased the significance of the coronation and the book honouring the new king; however, producing them was expensive and time consuming.

The production process reveals that the main focus was clearly more on the ceremonial presentation rather than a realistic portrayal of the event itself. Johann von Besser personally attended the event and based the book on his own observations. Whether the artist Johann Friedrich Wentzel (1670–1729), who created the drawings for the series of illustrations, also attended the ceremony remains uncertain to this day. The copperplate engraver Johann Georg Wolfgang (1664–1744) joined the court in 1704 and based his plates, of which he made a limited number of copies, on the drawings by Johann Friedrich Wentzel.

The path to the crown

The desire for equality

Friedrich, who came from the House of Hohenzollern, felt he had a rightful claim to the crown: the kinship, political alliances, large territories, military strength, and magnificent court were all features worthy of a King. As a German Kurfürst (elector) he was on the same level as a king but under the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor. However, other European Princes did not regard the status of ‘elector’ as equal to that of ‘king’. The end of the 17th century signalled a change in the European hierarchical system as William of Orange ascended the English throne and the Saxon elector ascended the Polish throne, driving Friedrich to strive for his own crown.

The first failed attempt

Friedrich’s first attempt to become king was thwarted by Kaiser Leopold I in 1693. Even though Friedrich desired a kingdom, which was independent from the emperor and his lands, the emperor’s consent was imperative. For a title meant nothing if not acknowledged by others. The emperor’s approval would ensure that Friedrich’s elevated status was swiftly recognised by the other European princes.

Success at last!

In 1698, the Elector of Brandenburg was able to use to his advantage the dispute between the emperor and the French King about the heir to the King of Spain, Karl II. After the death of Karl II on 1 November 1700, the Holy Roman Empire and France were on the verge of a military conflict. The emperor was under pressure and needed the support of the Elector of Brandenburg. Negotiations about the Prussian kingship were brought to a swift conclusion. In the so-called Krontraktat of 27 November 1700, an agreement between the emperor and Friedrich, the emperor gave his approval. In return, Friedrich pledged to give military support to the emperor if the dispute about the Spanish heir resulted in a military encounter.

Friedrich I, King in Prussia (1657–1713)

Friedrich, who was from the House of Hohenzollern, became Elector of Brandenburg (Friedrich III) in 1688 and King in Prussia (Friedrich I) in 1701. He was not unlike the other princes of his time with a pronounced desire for prestige and very conscious of his status. Becoming the first King in Prussia was one of the biggest successes of his rule and an important step towards unifying the dispersed territories of Prussia and Brandenburg since these areas were simply held together by the elector himself and had no collective name.

Brandenburg and Prussia prospered culturally under his rule. Friedrich invited artists and scientists to his court, transforming Berlin into a Residenzstadt in the Baroque style. The impressive royal court, grand Residenzen, and luxurious lifestyle became Friedrich’s status symbol. However, these came at great expense. Therefore, his rule was also characterised by poor state finances and corruption.

Johann von Besser (1654–1729)

Johann von Besser was greatly admired for his expertise in European ceremonials and was appointed the first master of ceremonies at the Brandenburg court. He was responsible for introducing foreign ambassadors and envoys at court and for establishing the Hollenzollerns’ place in the hierarchy of European rulers. As head of ceremonial proceedings planning and choreographing the coronation of the Prussian King was the highlight of his career.

Portrait of Johann von Besser,

copperplate engraving

by Martin Bernigeroth,

before 1733.