10

Composers – resonating through the ages:

Musical Estates in the Staatsbibliothek

Whether it be a diary, photo or letter, a bill, a true transcript, or a hastily drawn sketch – time and time again new aspects of musical history can be discovered in the musical estates of composers, bringing the past back to life. Of interest are the relationships and cross connections between individual musical estates and personalities.

The collection of great composers, such as Beethoven and Mendelssohn, prove to be fascinating even to the present day. One day numerous musicians and composers wish to find their works and documents in ‘good company’ in the Music Department of the Staatsbibliothek.

To this day, the Music Department holds around 500 estates, collections, and items deposited either by personalities or institutions of music history. Some of its holdings are very comprehensive and include the most diverse testimonies. Surviving relatives often arranged and preserved archival items in proper order. It is not infrequent that a transfer happens in several stages. Many estates document not only the life and work of musicians, composers, and musicologists, but also document the music history as well as the contemporary history of Berlin at the beginning of the 20th century and are therefore of major importance.

The musical estates create an extremely vivid picture of music from quite different time periods. Alongside the papers of the great and famous, there are the estates of lesser-known composers.

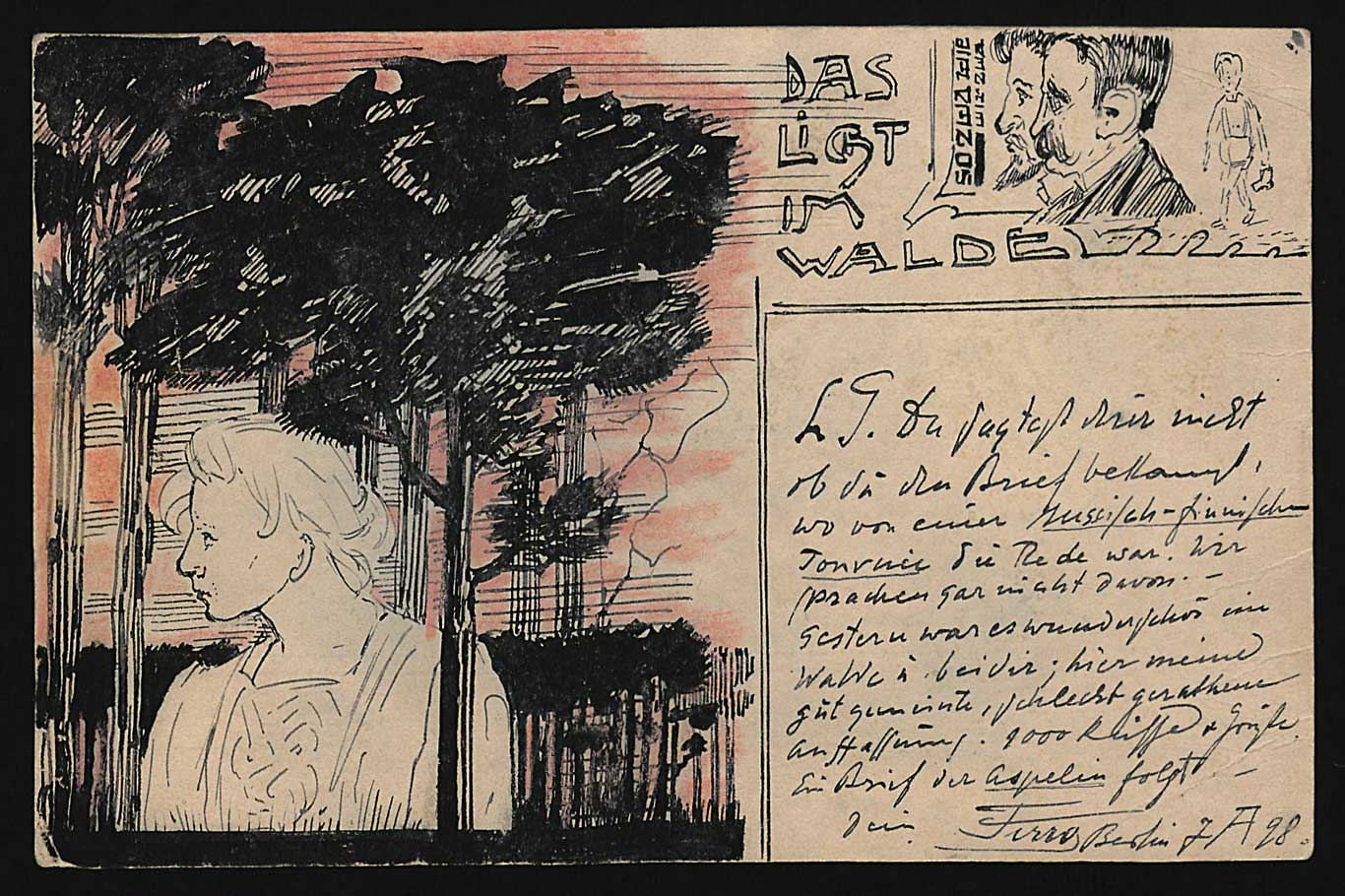

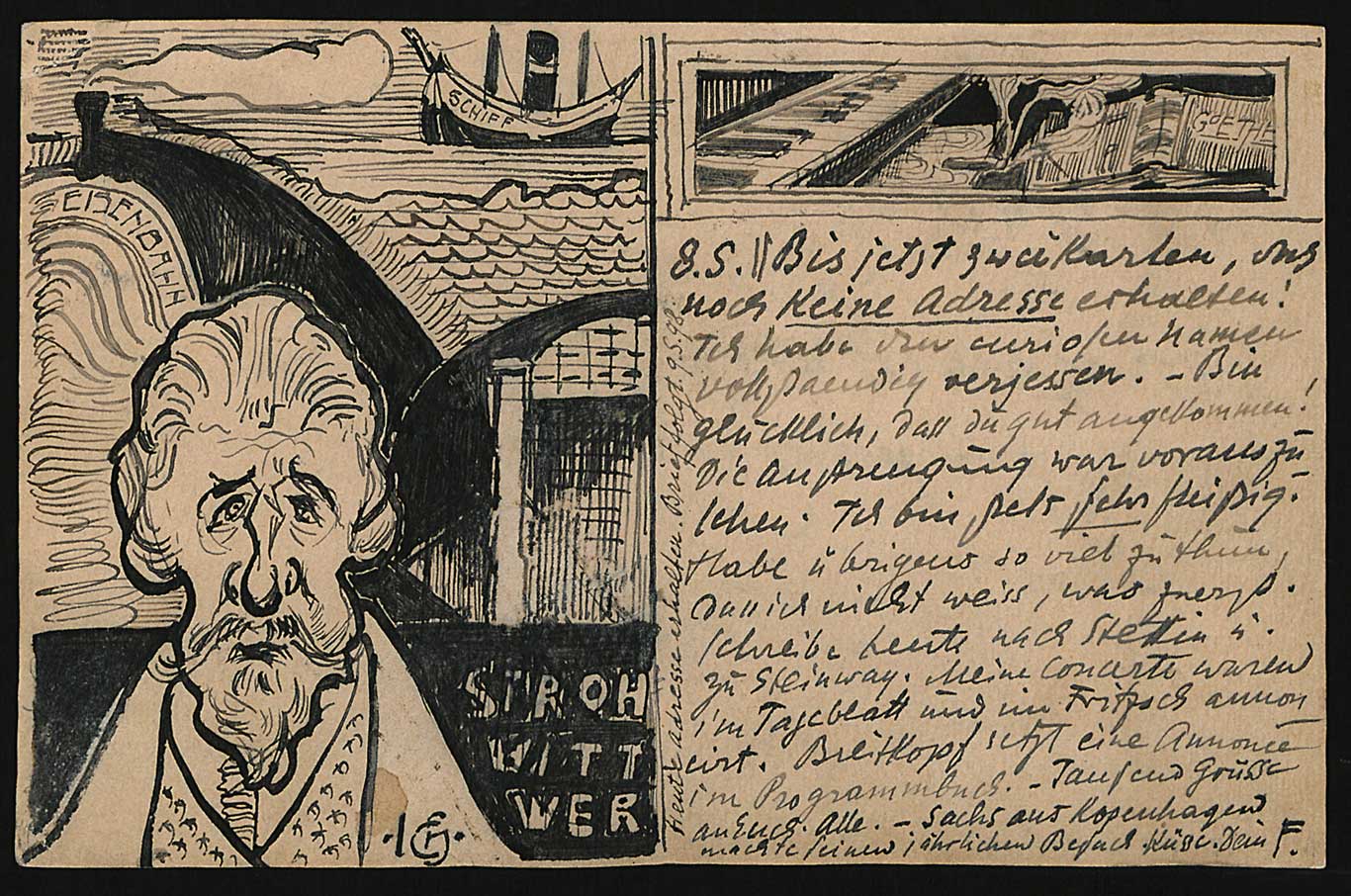

The musical Estate of Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio Busoni was a celebrated pianist, composer, editor, teacher, and writer of music. Due to his numerous concert tours and masterclasses (for example in Helsinki, Bologna, Moscow, and Boston), Busoni spent weeks on end abroad. Travelling through the United States of America was particularly strenuous since he was on a very tight schedule. This left him with very little time to send letters to his wife Gerda to whom he usually liked to describe his experiences and encounters in detail. The constant travel was a great burden to Busoni and severely affected his health. In addition, he had to take a break from composing, which resulted in fatal consequences. One of the projects he was working on was the opera Doktor Faust, which he had been composing for the last two decades of his life and was unable to finish. After Busoni died, his pupil Philipp Jarnach completed the opera in 1925.

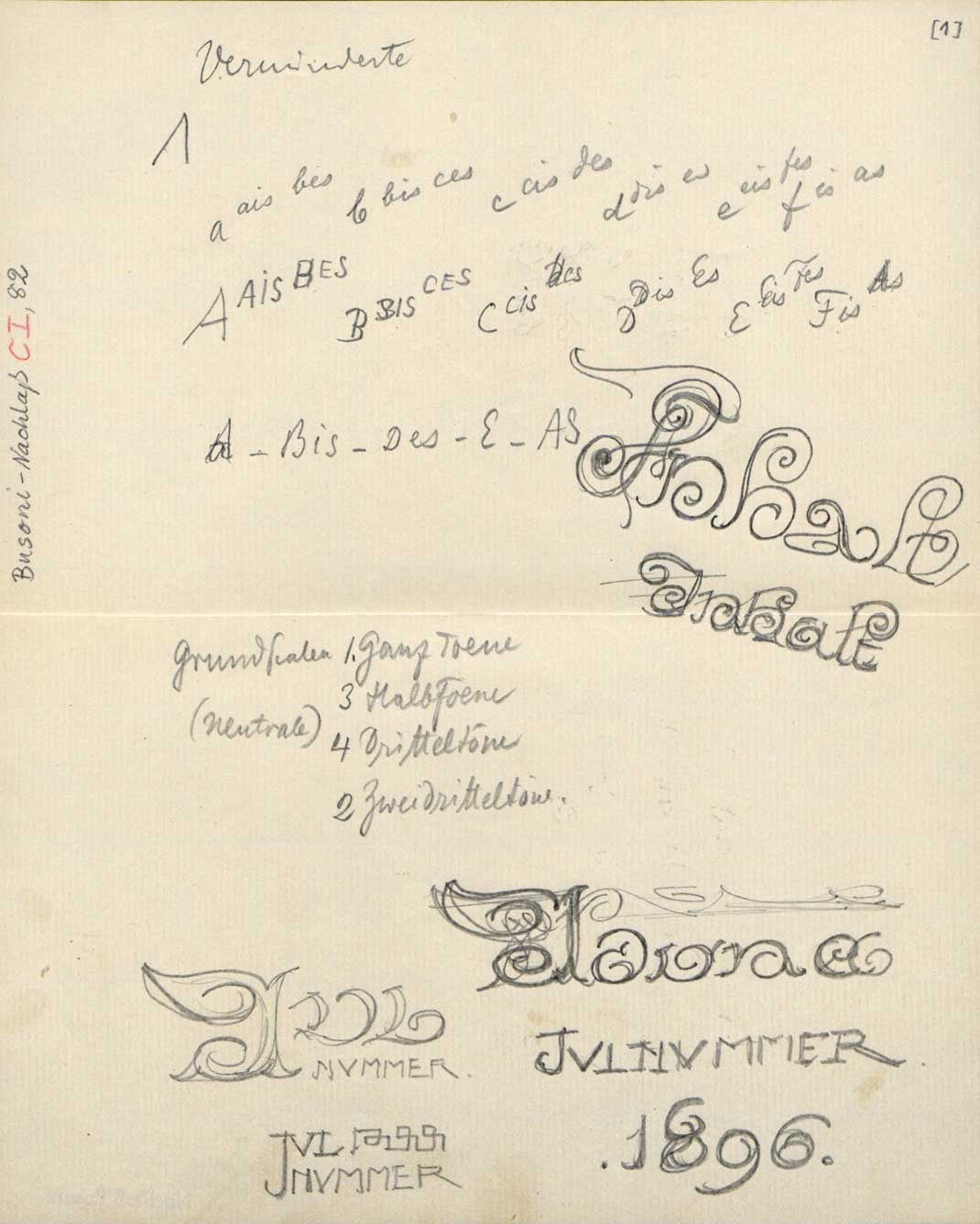

At the centre of Busoni’s musical contributions is his essay on the concept of Neue Ästhetik der Tonkunst (New Aesthetics of Music). It was not until the second edition was published by Insel Verlag in Leipzig in 1916 and dedicated to the poet Rainer Maria Rilke that his essay became a topic of interest. Busoni put forward the idea of a broader sense of pitches and a Dritteltonharmonium (harmonium to produce thirds of tones). The concept was followed by a heated discussion and rejected by many (Hans Pfitzner, Futuristengefahr). In response to the critics Busoni replied: „First: can we do what they did in the past and as well before we start composing new pieces? Second: are we even talented?”

Putting his ideas on the aesthetics of music into practice proved to be extremely difficult. In 1915, the first Dritteltonharmonium was created specifically for Busoni in New York but the technology was very complex. Busoni’s idea may be regarded as a stepping stone towards the development of electronic music and a milestone in the history of music. When it came to his own compositions, Busoni was a traditionalist and never incorporated a Dritteltonharmonium.

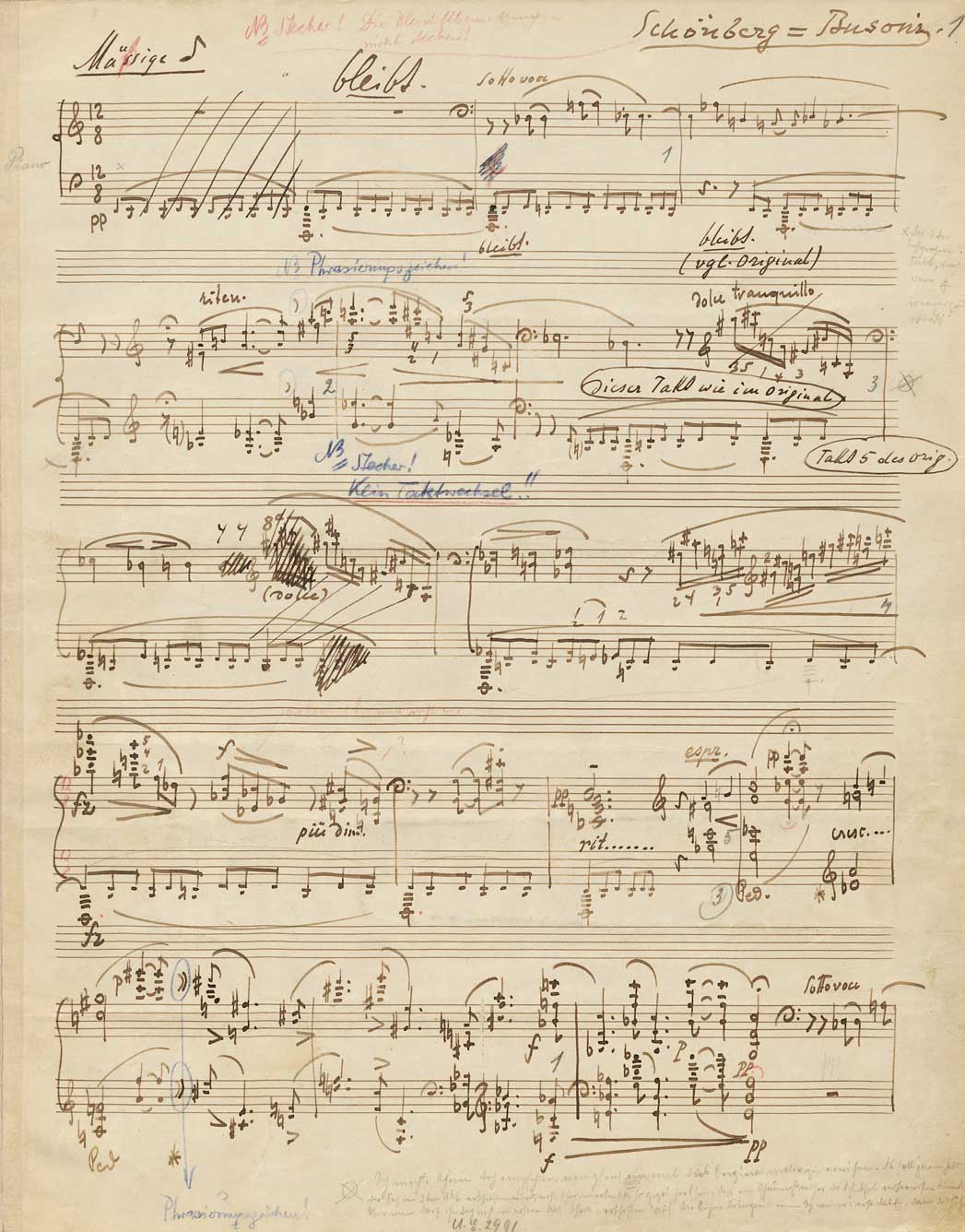

The composer Arnold Schönberg was searching for a worthy pianist to give the first performance of his piano piece op. 11. Schönberg sent the complete composition to Busoni for he believed he had found a comrade-in-arms who would spectacularly interpret his musical innovations. Despite Schönberg’s high hopes, the concert did not take place. Instead, Busoni edited the second piano piece of op. 11, having found deficiencies in Schönberg’s composition. Busoni said that as a pianist it was his duty to give more emphasis to the changing sound quality by transforming chords into musical figures and including octaves. The doubly edited autograph from the year 1909 documents the fruitful exchange between the two composers.

The majority of Busoni’s estate came to the Preußische Staatsbibliothek between 1925 and 1943 thanks to his widow Gerda Busoni. His estate consists of handwritten musical notations, libretti, writings, letters, biographical material, portraits, concert programmes, and critical comments. Over the years more material has been acquired, continually expanding the Busoni estate. The sheer amount of material shows the broad spectrum of the intellectual-artistic world of the avant-garde up to the beginning of the 20th century.

Ferruccio Busoni: edit of the piano piece op. 11 no. 2 by Arnold Schönberg, 26 July 1909. digital copy

The musical estate of the Comedian Harmonists

The story of the Comedian Harmonists started with the musical autodidact Harry Frommermann, who put a small announcement in a local Berlin newspaper on 29 December 1927. He was inspired by jazz music, finely tuned timbres, and imitation of sounds produced by the American quartet The Revelers. Frommermann wished to create a German equivalent.

More than seventy variously talented singers came to audition. However, only the bass singer Robert Biberti lived up to Frommermann’s artistic expectations. Biberti, a confident and skilled negotiator, saw himself as the leader of the evolving group. He meticulously archived all the group’s material, such as notes and business documents for their future musical estate.

Biberti made use of his contacts and acquired the velvety soft tenor Ari Leschnikoff and the beautifully sounding baritone Roman Cycowski. The group was later joined by the second tenor Erich Collin and the talented pianist Erwin Bootz. The Comedian Harmonists were the first internationally successful ‘boy band’ in the world.

Comedian Harmonists: Mein kleiner grüner Kaktus, 1934. digital copy

At the time it was not widely known that Collin, Frommermann, and Cycowski were Jewish. With the rise of the Nazis, the group met with ever increasing disapproval and ultimately rejection. Concerts under contract began to be cancelled.

Comedian Harmonists: Morgen muss ich fort von hier, um 1935. digital copy

All six Comedian Harmonists had applied for membership in the Reichsmusikkammer (Reich’s Music Department) but in February 1935 only the ‘Aryan’ members Biberti, Bootz, and Leschnikoff were accepted. They were prohibited from performing with their Jewish colleagues as the Comedian Harmonists. The non-Aryan members fled the country, and the fate of the group was sealed.

Letter, banning the Comedian Harmonists from working, 22 February 1935.

digital copy