Checking, distributing, exchanging:

the role of the Preußischen Staatsbibliothek

Nazi loot in the

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

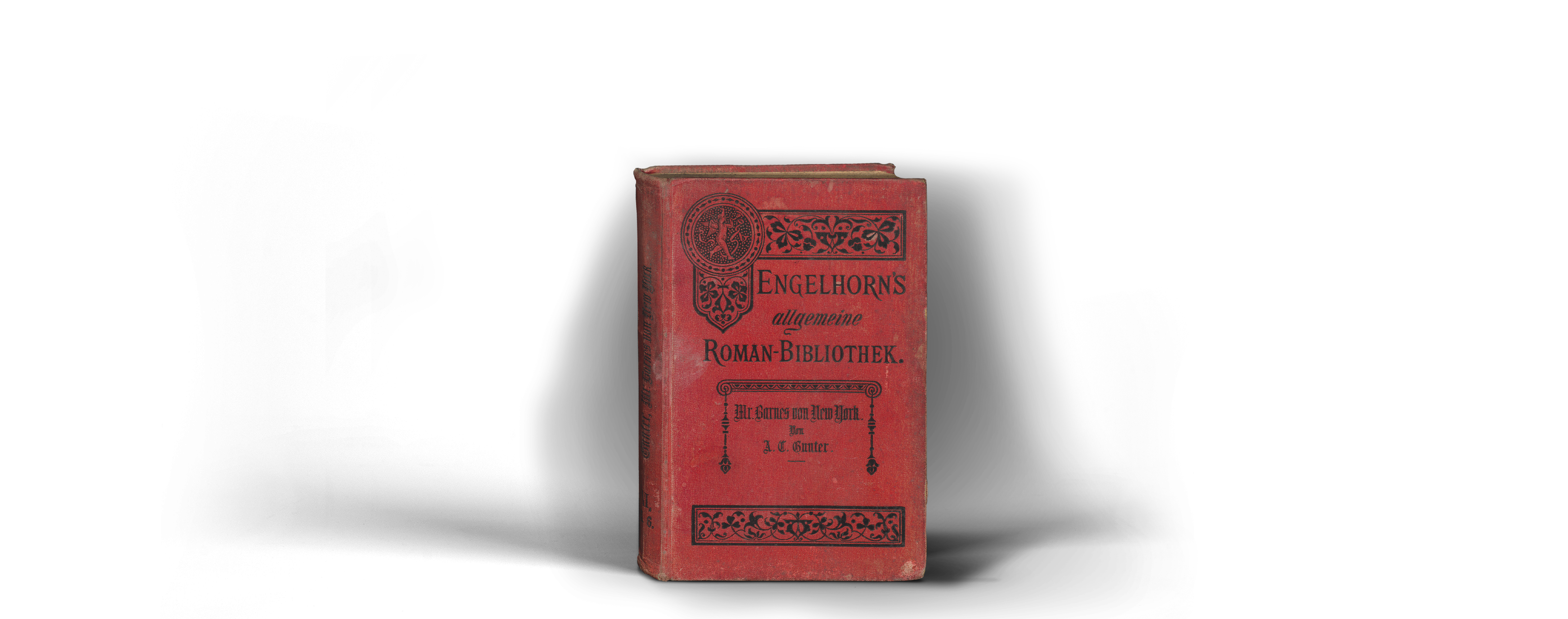

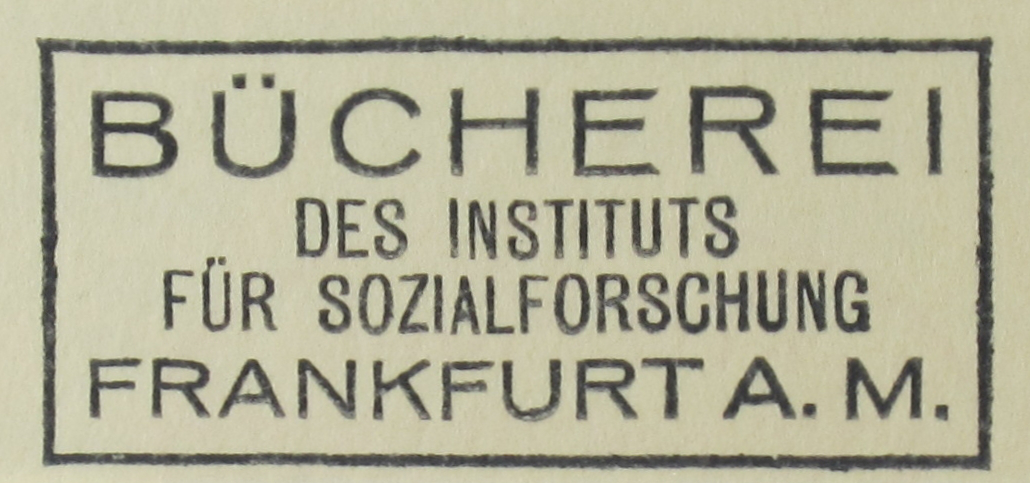

Stamp of the Secret State Police (Gestapo). SBB-PK / Thomas Rose. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

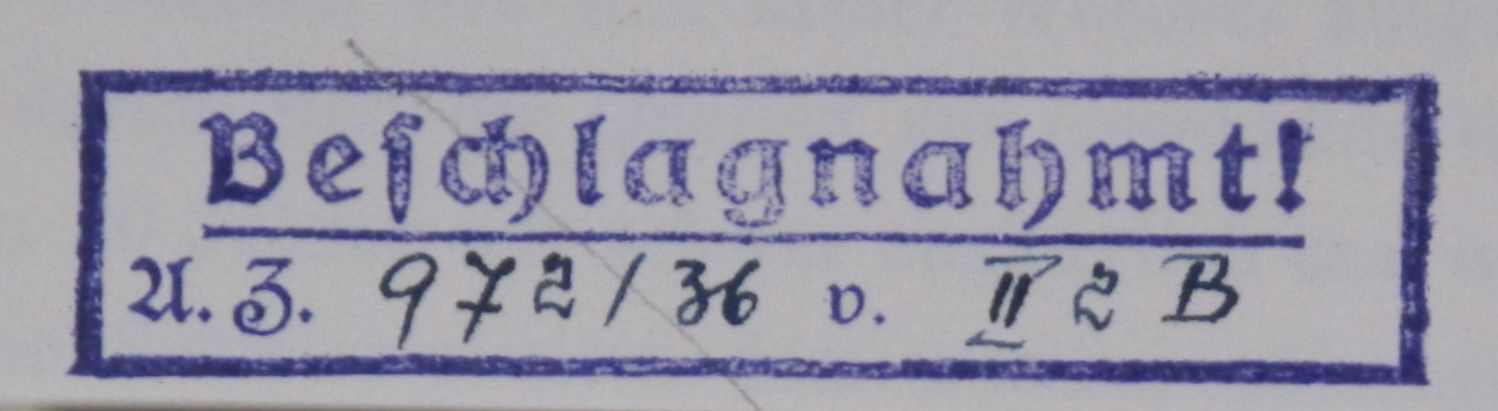

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, books were redistributed on a very large scale. During this process, the Preußische Staatsbibliothek as the most important library in the German Reich, was the centre of operations for receiving and distributing confiscated literature. With the introduction of the Reichstauschstelle, a further central distribution centre was set up. There were two ministerial decrees in the year 1934, which coordinated how to make use of the seized assets of communists as well as of ‘Volksfeinde’ (individuals and institutions the Nazis regarded as enemies of the people). Two more decrees followed in 1938 and 1939 respectively, which were concerned with confiscating Jewish and Hebrew literature. Taking these decrees into account, it was decided that the Preußische Staatsbibliothek was to accept books confiscated in Prussia. The authorities concerned reported the titles of such works to the Preußische Staatsbibliothek. The library accepted and incorporated any works, which fit the requirement profile and were not yet part of their collection. Most books were allocated to other research and academic libraries.

The local police authorities usually only contributed a small amount (confiscated material from the local offices of the SPD, publishers etc.). Especially books purposefully arranged in a complete set were worth more than the total sum of the individual copies. So, the Preußische Staatsbibliothek focused on acquiring high-quality, complete collections. However, this was rarely successful. In addition to the Preußische Staatsbibliothek, other institutions, which were also responsible for dealing with confiscated literature had been newly founded by the Nazis, for example the Bibliothek des (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamts or the Hohe Schule. This rivalry often led to the break-up and destruction of collections, which had grown over time.

Reichstauschstelle

In 1926, the Reichstauschstelle was established by the library board of the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft and was initially in charge of the distribution of literature. In the beginning, the Reichstauschstelle mainly dealt with the library collections of disbanded public offices and companies. By the end of the 1930s, it made also looted books available to interested libraries. In the 1940s, the Reichstauschstelle had developed into a more autonomous institution for acquiring literature during the rebuilding programme of German libraries, which had been destroyed because of the war.

(Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt

The Reichssicherheitshauptamt was a central office of the SS (Schutzstaffel), acting as an intelligence and security service. Initially called the Sicherheitsdienst of the SS, it was restructured and renamed the Sicherheitshauptamt in 1939. For the so-called ‘adversary studies’ collection and the training of police and SS, the Sicherheitsdienst established a central research library in Berlin, whose collections were founded on confiscated and politically undesirable printed works.

The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, which succeeded the Preußische Staatsbibliothek, is committed to working through and fully understanding the issue of cultural property confiscated due to Nazi persecution. Nazi loot is identified, documented, and restitued. The Staatsbibliothek examines the way in which Nazi loot is distributed and what basic institutional and administrative processes were established. As part of this, the Staatsbibliothek is working on developing methods of identifying and recording the provenance of library collections in cooperation with other libraries.

Current news

Current information about the provenance research in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin can be found in the Newsroom (German only).

A letter from the local police authority in Münster on 27 September 1934 to the Preußische Staatsbibliothek, announcing the confiscation of Marxist books. SBB-PK

Confiscation, theft, and redistribution of Nazi loot

Persecuted and robbed

At the beginning of the Nazi regime, people and institutions, considered political adversaries, such as social democratic and communist parties and associations, and labour organisations, were affected by the looting. In addition, organisations such as the freemasons and other philosophical institutions with opposing ideologies were persecuted. However, no ethnicity was so heavily targeted as the Jewish population. Antisemitic riots, the boycott of Jewish establishments, the Nuremburg Racial Laws etc. all led to the ostracism, persecution and banishment of Jews in the German Reich, culminating in the Pogrom in November 1938. This was followed by the deportation and murder of millions of people in concentration camps.

Seizing valuable property, such as book collections was a method of persecution and oppression. The displacement of the Jewish population in particular was systemically supported by the state and so made the theft of Jewish property legal.

‚Detrimental and undesirable printed works‛

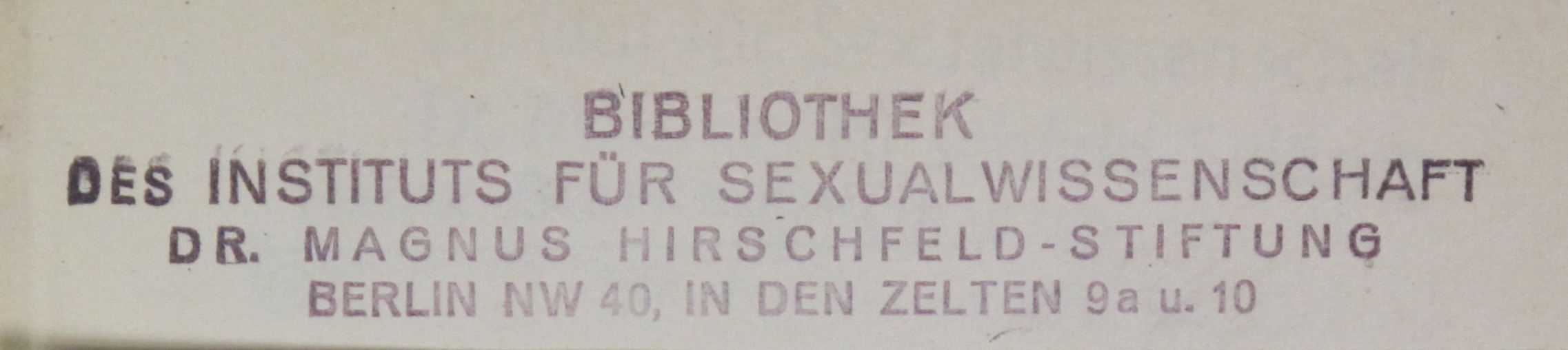

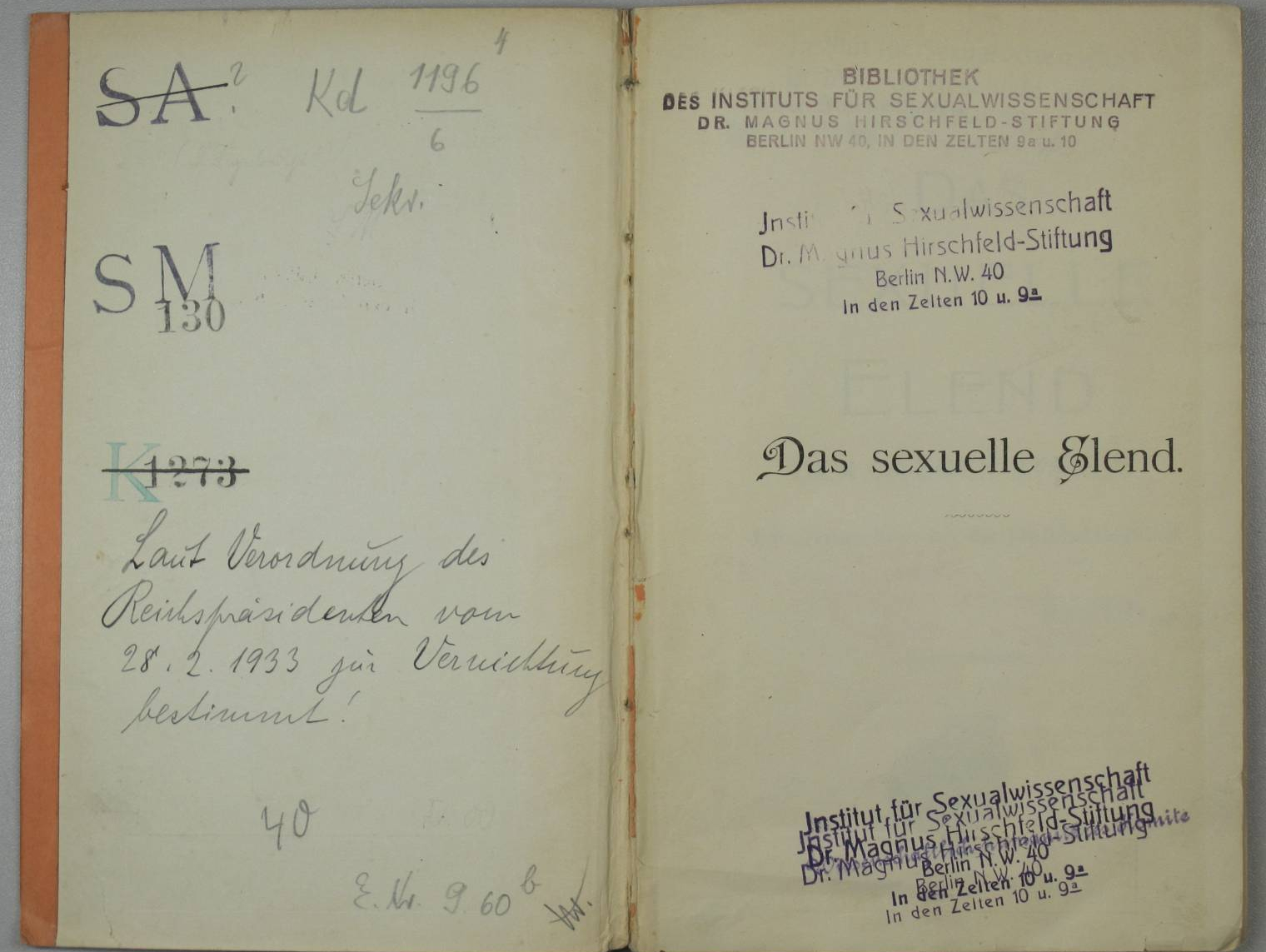

Censorship and destruction of the library of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

The library of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, which had been founded by the doctor and sexologist Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935) in 1919 in Berlin, fell victim to these ‘purges’. The library, which had been especially established at the institute for the research of Sexology, was plundered and ransacked by students on 6 May 1933. In the afternoon, a SA (Sturmabteilung) unit took over and continued the looting. Some of the books were burned on the Opernplatz in Berlin on 10 May, while the rest of the books was checked and then handed over to the Berlin tax office under the pretext of unpaid taxes. The books were either put up for auction or simply sold.

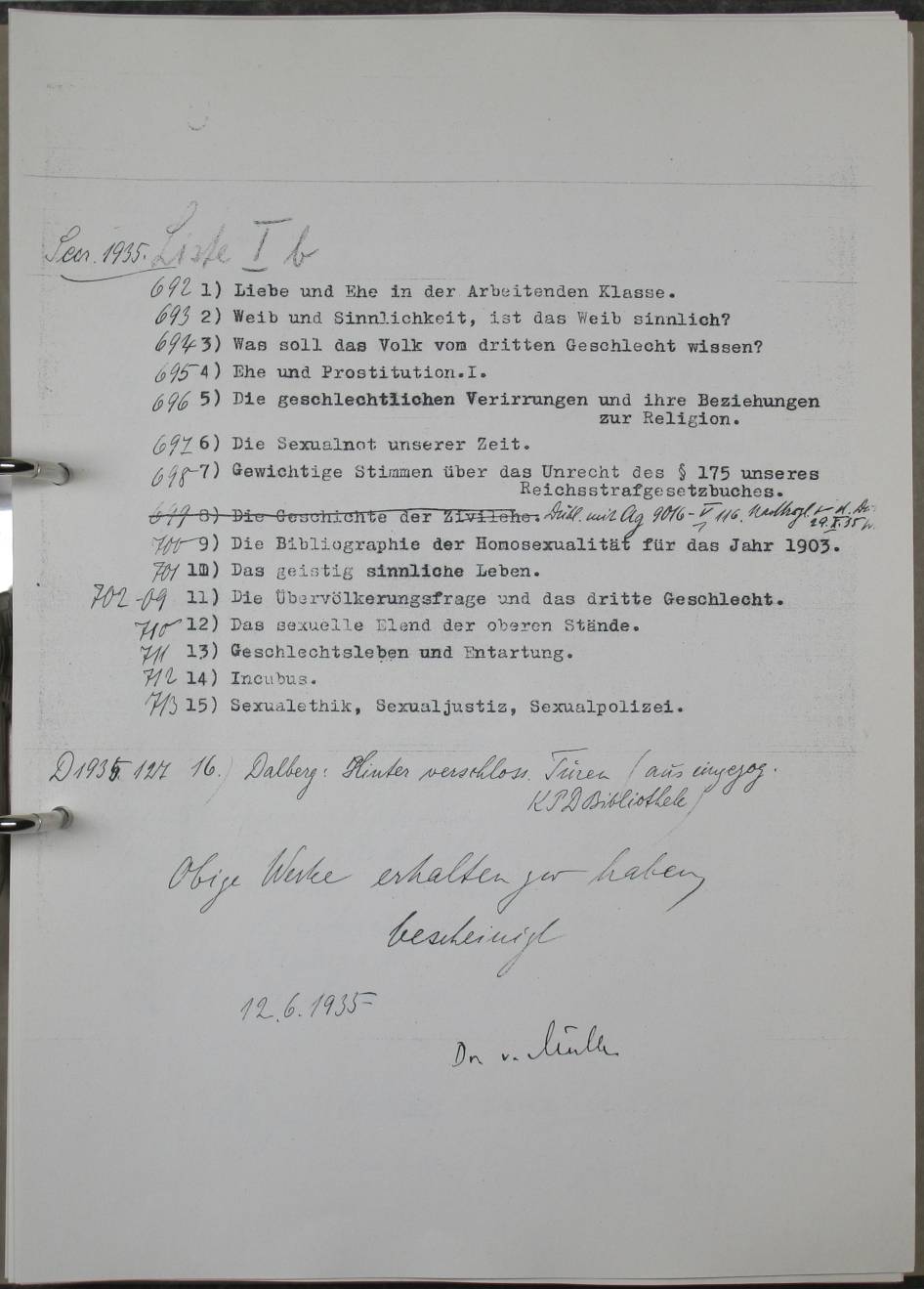

In 1935, several volumes came into the possession of the Preußische Staatsbibliothek, which were classified as forbidden literature. The books were stored separately and kept under lock and key. The reading of such books was limited to a few select ‘trustworthy’ people. Some of these volumes are no longer in the Staatsbibliothek because they were transported out of Berlin during the bombing and did not return after the war.

There is no catalogue of the former library of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, which makes the reconstruction of its collection extremely difficult. So far, the books belonging to the library have not been fully located and a few copies continue to turn up in antiquarian bookshops.

Like to find out more? Then take a look at ProvenienzWiki! (German only)

The books were given a ‘Secr.’ accession number. It was often written inside the book and is used today by researchers to identify copies of Nazi loot.

Here the Preußische Staatsbibliothek acknowledges that it received all listed forbidden works.

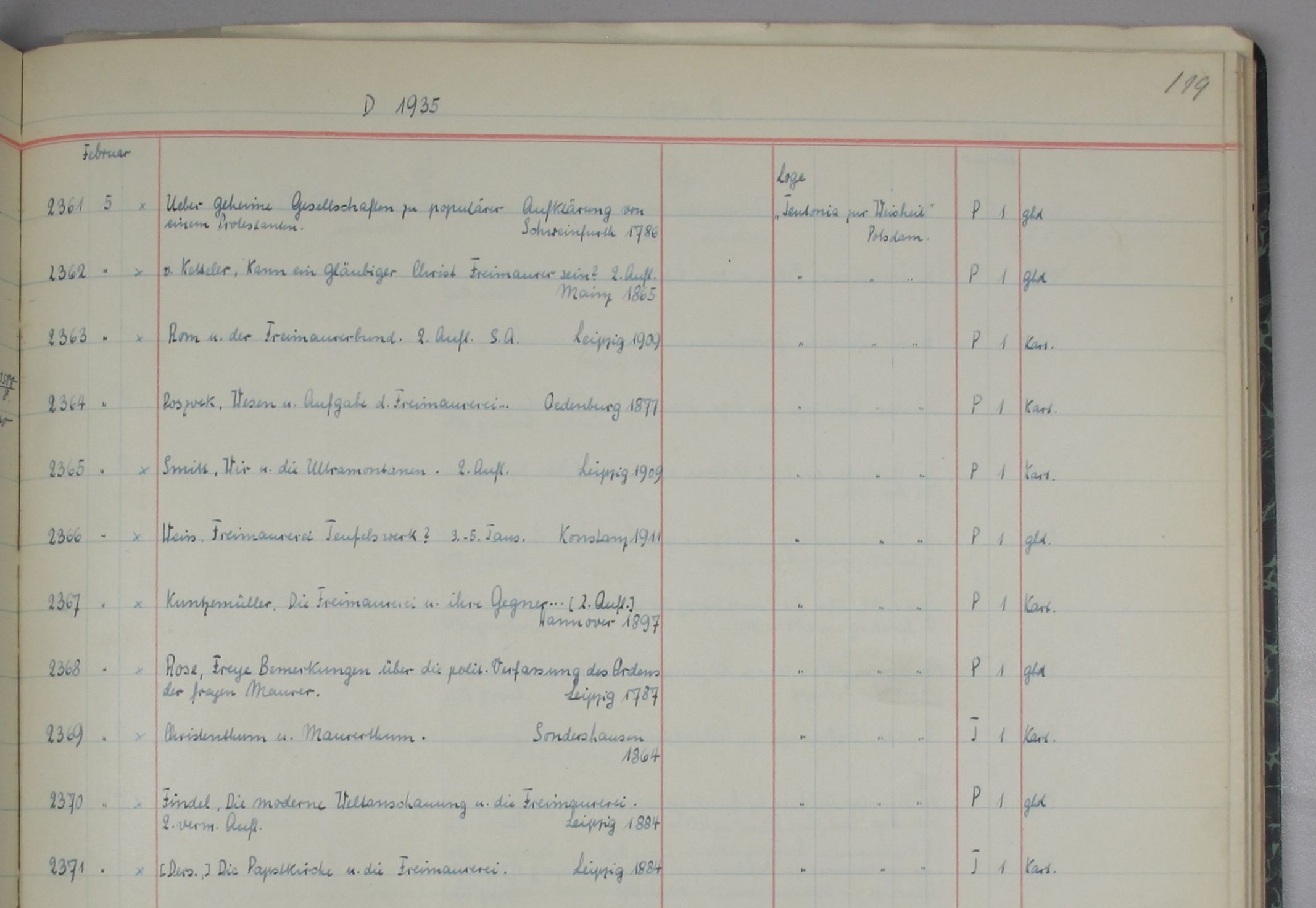

This list records the arrival of 15 forbidden works from the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft in the Preußische Staatsbibliothek in 1935. Preußische Staatsbibliothek, Sammelbearbeitungsliste Ib, 12.6.1935. SBB-PK

Heinz Starkenburg, Das sexuelle Elend der oberen Stände. Ein Notschrei an die Öffentlichkeit, Leipzig 1898. SBB-PK / Michaela Scheibe

Seizing ‘subversive’ assets

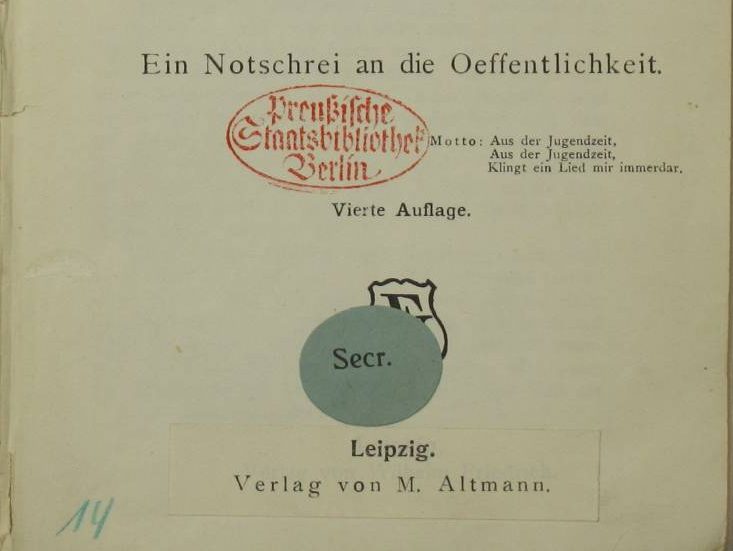

The break-up of the library of the Institut für Sozialforschung in Frankfurt am Main

From the very beginning of its foundation in 1923, the Institut für Sozialforschung (IfS) in Frankfurt am Main has been committed to exploring the theory and history of socialism and the labour movement. This also included the study of Marxism. In 1930, under Max Horkheimer the institute developed into an intellectual centre and became known throughout the world as the so-called Frankfurter Schule.

As the institute’s research focus was closely related to the current political situation, the institute was declared ‘subversive’ and disbanded on 13 March 1933. The valuable collections, including rare material such as revolutionary leaflets, were confiscated.

In 1937, the Preußische Staatsbibliothek received mostly ‘subversive’ literature, whereas any material deemed harmless were handed over to the university departments in Frankfurt. If the Staatsbibliothek had more than one copy of the same book or the volume was considered to be of little significance, they were given to the (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt to be added to their ‘adversary studies’ collection. After the Second World War, such Nazi institutions were disbanded, and these books further distributed to other academic and research libraries. Some copies found their way to the Zentralstelle für wissenschaftliche Altbestände. Therefore, it is possible that books acquired after 1945 were also Nazi loot.

ZwA number

The ZwA number was often written inside the books.

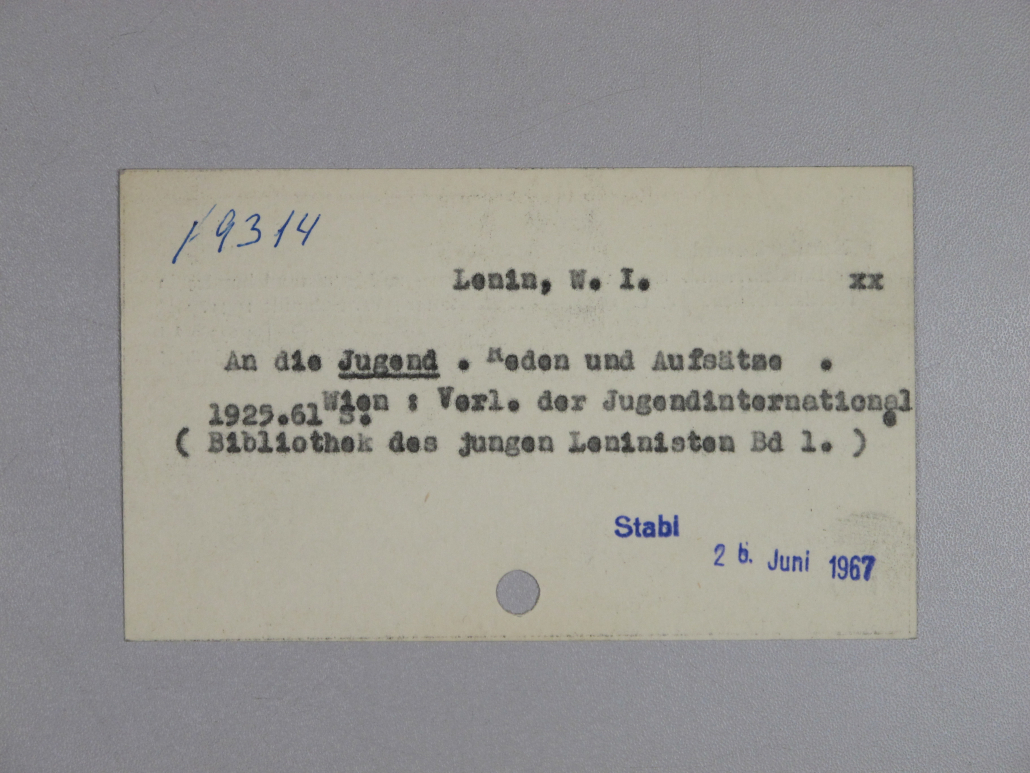

Any books received by the Zentralstelle für wissenschaftliche Altbestände (ZwA) were entered in the ZwA catalogue on a title card and given a (ZwA) number. Katalogkarte der ZwA. SBB-PK / Thomas Rose. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Zentralstelle für wissenschaftliche Altbestände

From 1953 to 1995, the central exchange office for libraries in the GDR organised the acquisition of duplicates and books regarded as ‘ownerless’ to compensate for the lack of books in academic and research libraries after the war. Some of these books had been expropriated and confiscated during the Nazi regime. The Zentralstelle für wissenschaftliche Altbestände was located at the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek as of 1959, which was the predecessor of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

A selection of books from the Preußische Staatsbibliothek were relocated in the German Reich to protect them from aerial bombings during the Second World War. These books did not return to Berlin after 1945; however, the books, which had remained in Berlin, were organised and distributed according to the regulations of the SED regime in the GDR. A large number of Socialistica, some of which were Nazi loot, were used to set up new special libraries, such as the library of the Institut für Marxismus-Leninismus, founded in 1949.

Like to find out more? Then take a look at ProvenienzWiki! (German only)

Restitution

The library of the Institut für Sozialforschung, whose collections had been spread under the Nazi regime, was re-established in 1951 in Frankfurt am Main. This resulted in numerous restitutions; for example, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin returned 536 volumes to the institute in 2018.

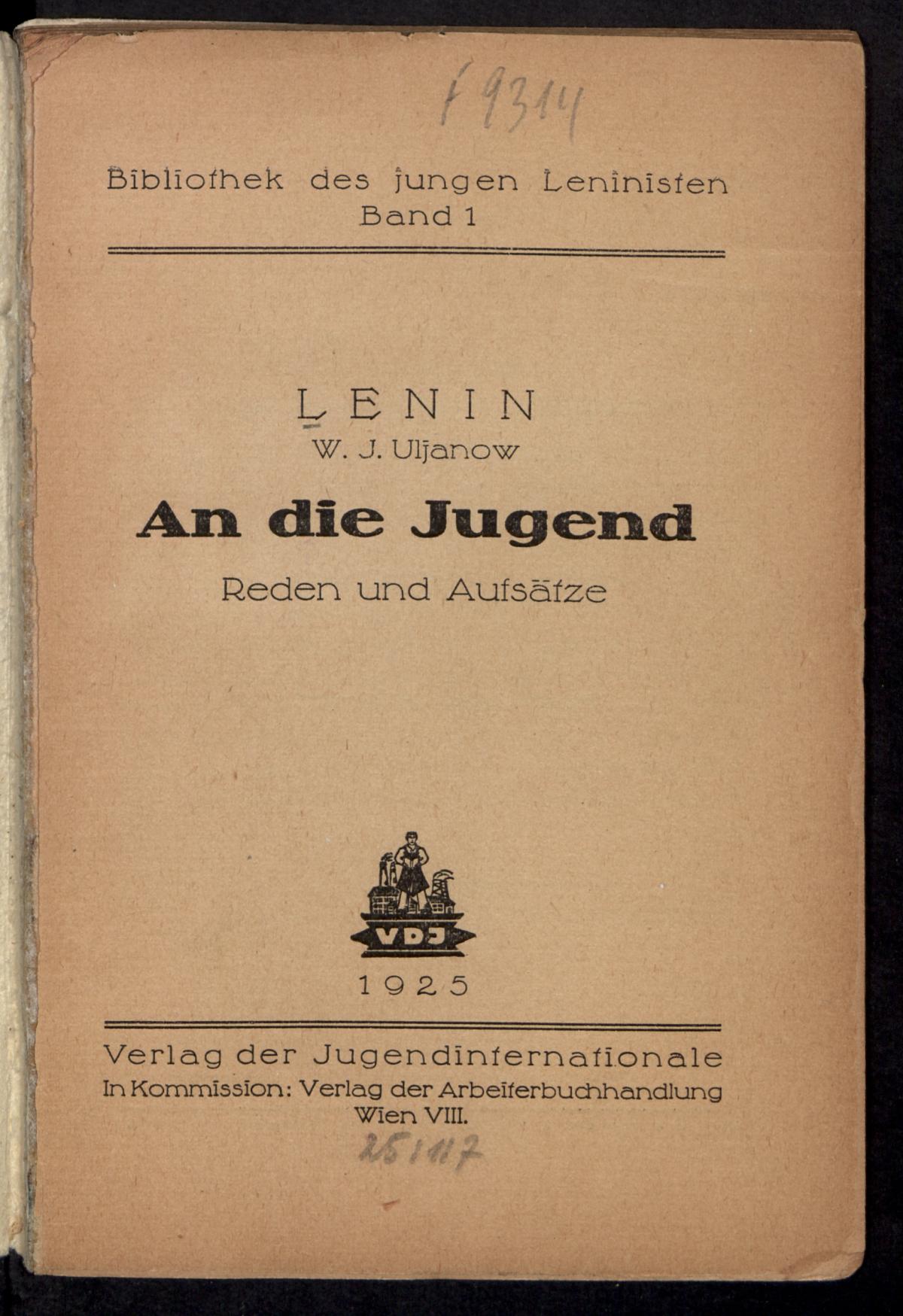

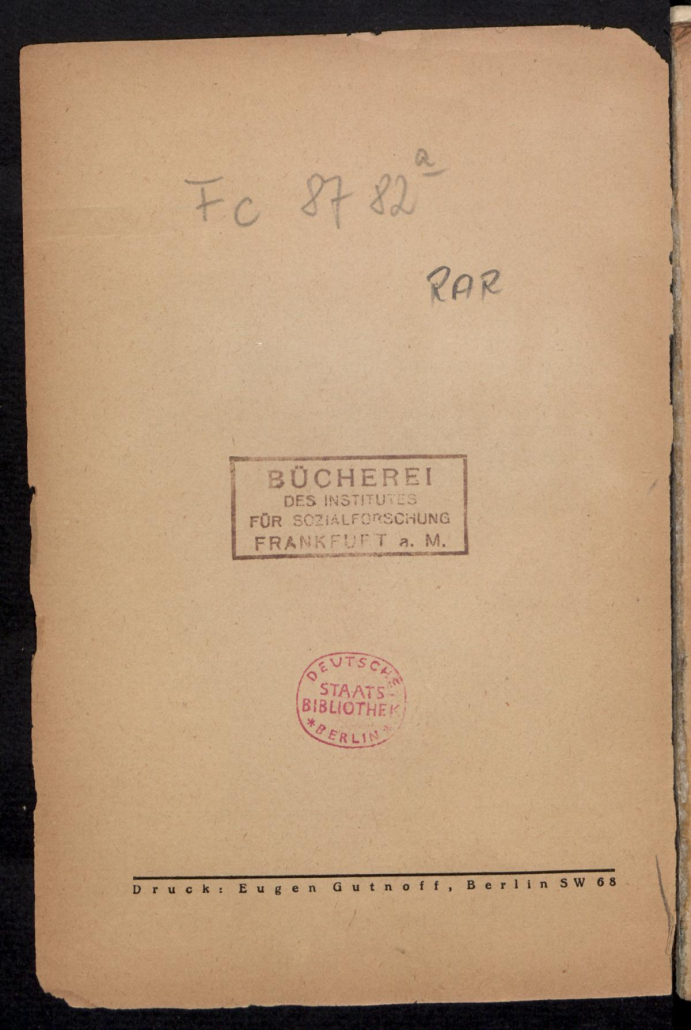

The Institut für Sozialforschung had its own accession number, written on the title page in pencil. This was an important clue in identifying copies from this institute.

The ZwA number was often written inside the books and today is used to identify the copies, which were distributed via the ZwA. The number provides information about the book’s journey after 1945. However, it does not reveal whether it is Nazi loot.

Another important clue in identifying copies from the Institut für Sozialforschung is the institute’s personal stamp on the back of the title page.

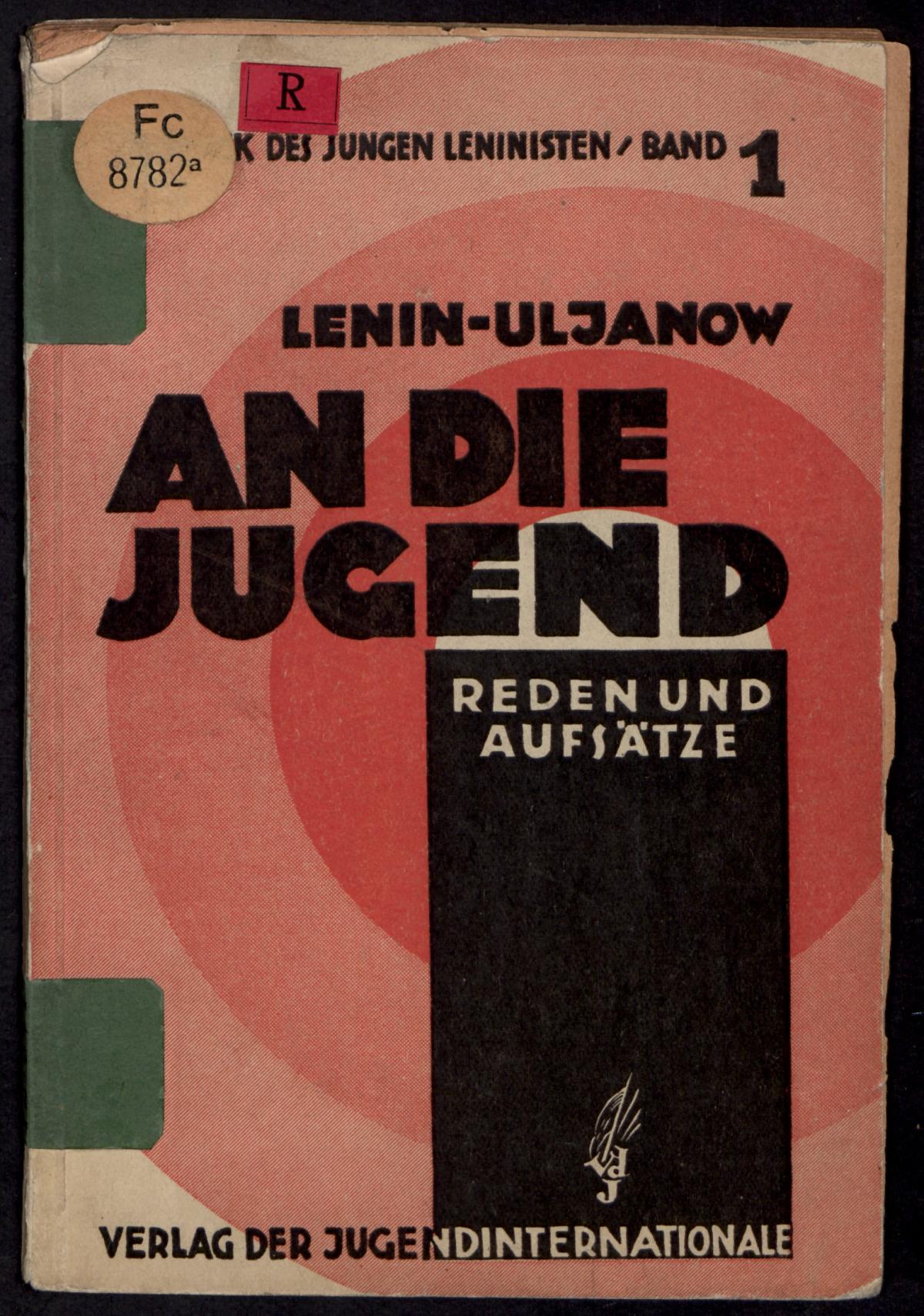

This book was originally from the library of the Institut für Sozialforschung and came to the Staatsbibliothek via the ZwA in 1967. Vladimir I. Lenin: An die Jugend, Wien 1925. digital copy

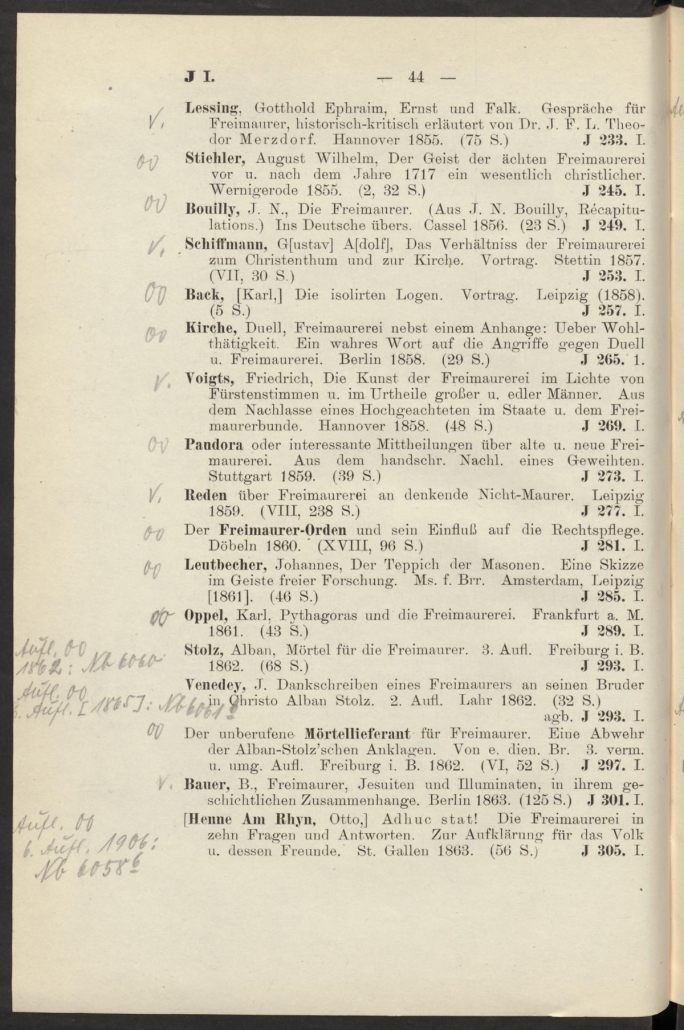

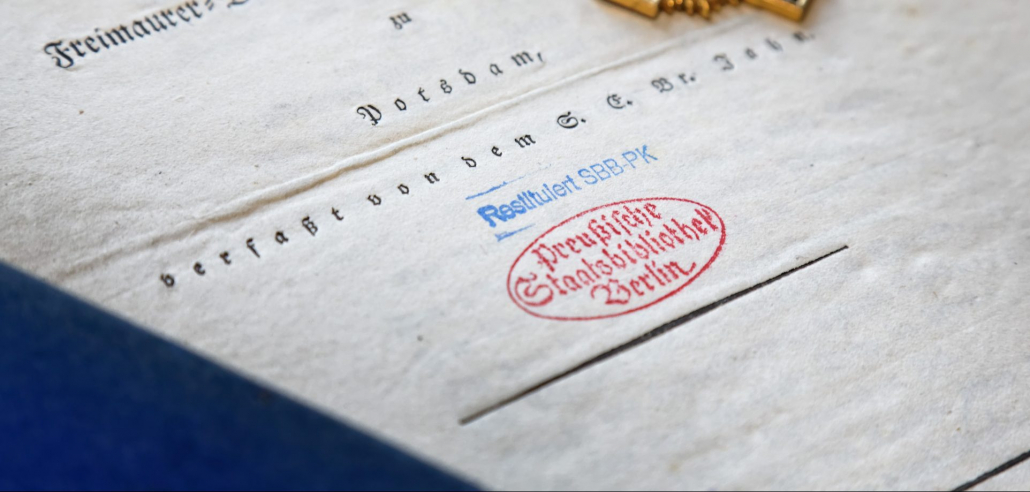

Masonic lodges: forced to disband

The Library of the Johannis-Loge Teutonia zur Weisheit in Potsdam

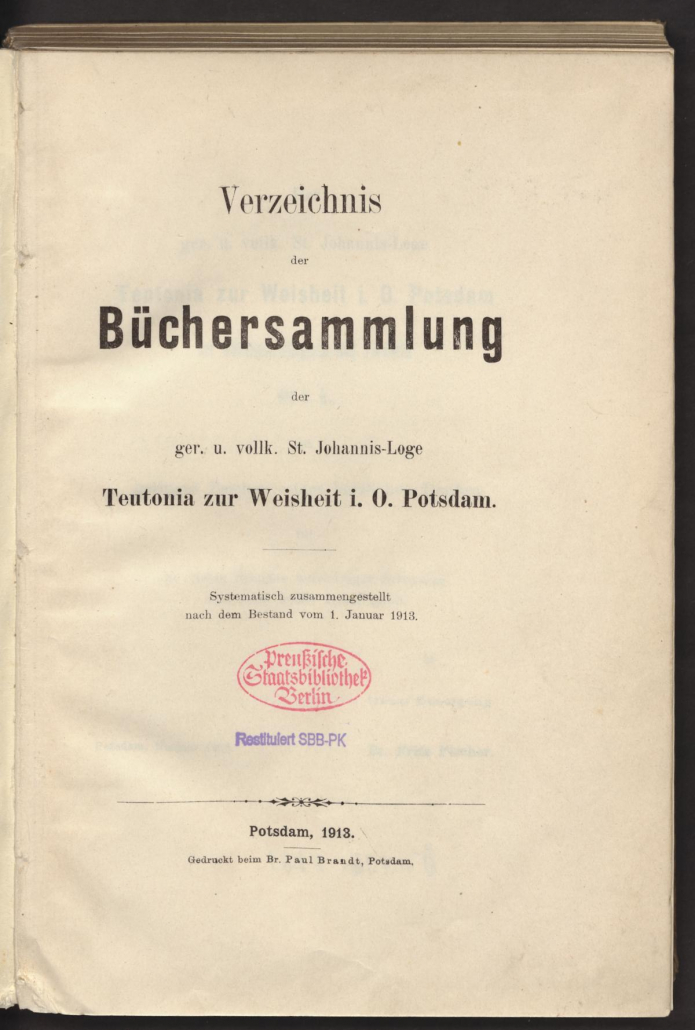

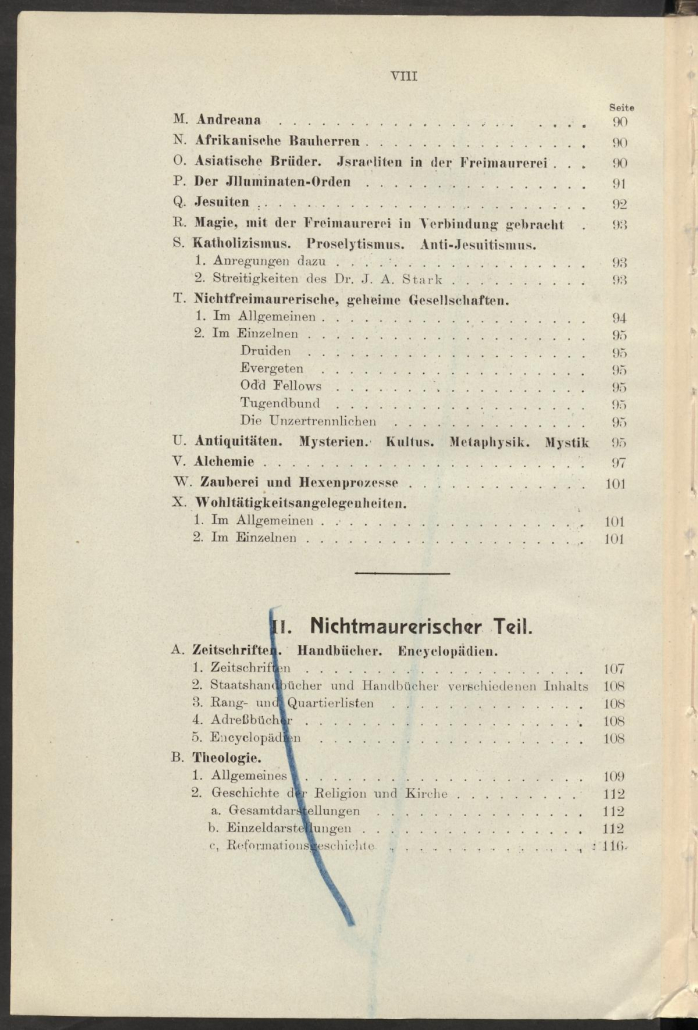

The German Masonic lodges had a long tradition. For example, the Johannis-Loge Teutonia zur Weisheit had existed since 1809 and owned an extensive and well-organised library.

In 1933, when the destruction and splitting up of library collections began, the lodge tried to prevent this by offering their books to the Preußische Staatsbibliothek. The lodge hoped the Staatsbibliothek would take and preserve the library’s entire collection. However, the Staatsbibliothek said it was only willing to take the Masonic literature of the lodge’s collection and even those works would not stay together in a special collection since any books with more than one copy were rejected and given to the National Library in Vienna.

This catalogue of the lodge’s books was probably used by the Preußische Staatsbibliothek to compare the lodge’s collection with their own collection before the transfer took place. St.-Johannis-Loge Teutonia zur Weisheit i. O. Potsdam, Verzeichnis der Büchersammlung, Potsdam 1913. digital copy

The Teutonia Lodge was a rare exception because it organised the disbanding of their library early on and so could decide what to do with a large number of their collection. Even though measures had been taken to protect the library, the splitting up of the collection could not be fully prevented.

Like to find out more? Then take a look at ProvenienzWiki! (German only)

Restitution

The Teutonia Lodge did not re-open until 1991 in Potsdam since the GDR did not allow it. Therefore in 1965, 639 volumes from the Staatsbibliothek in West Berlin were transferred to the Große National-Mutterloge. As a higher establishment it represented the lodges, which had not been allowed to reform. In 2016, after extensively researching the collections of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, another 384 books were identified and this time given directly to the Teutonia Lodge.

D = Dona (gifts) with the year of acquisition also reveals the title for the accession book

consecutive accession number

day of entry into the accession book in 1936 (fiscal year 1935)

bibliographical information on the acquired work

Information about the supplier

All acquired books, looted or otherwise, were recorded in the printed columns of large accession books. Every title was assigned a number. This number was also written inside the book and is useful in finding out the previous owner of volumes without an identification stamp. Preußische Staatsbibliothek, Akzessionsjournal Dona, 1935. SBB-PK

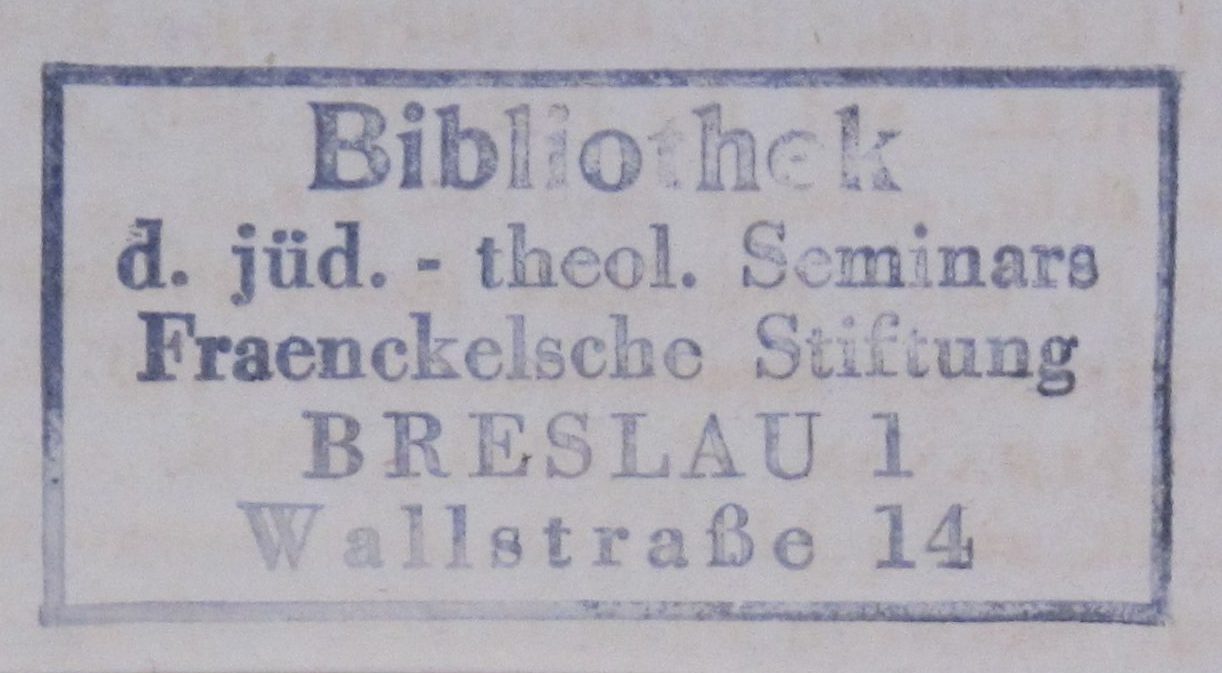

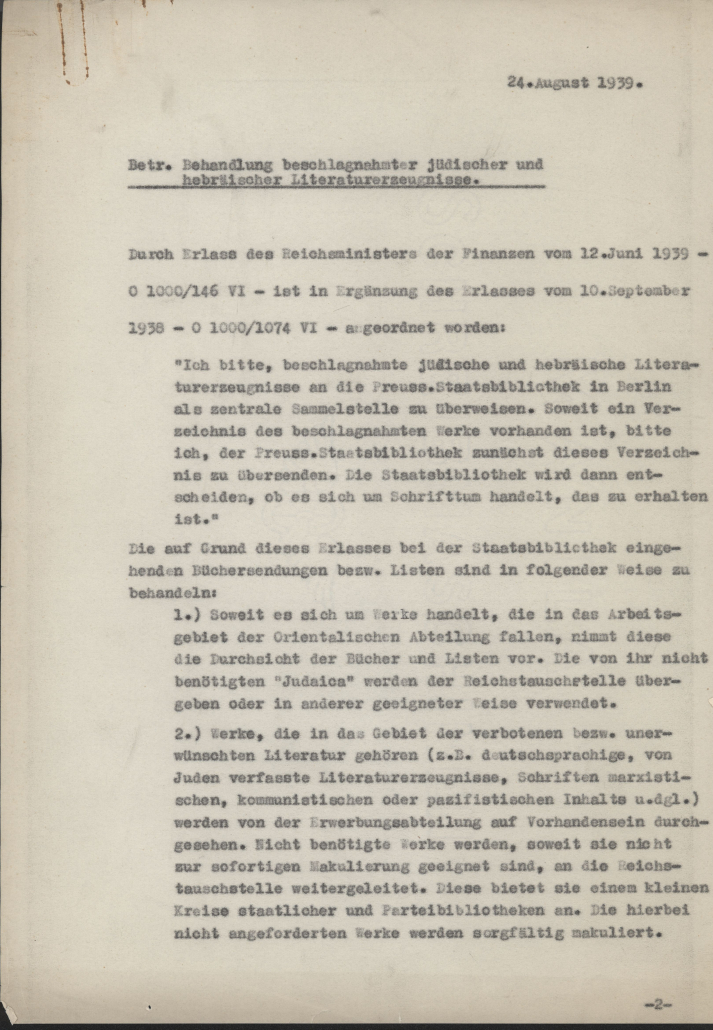

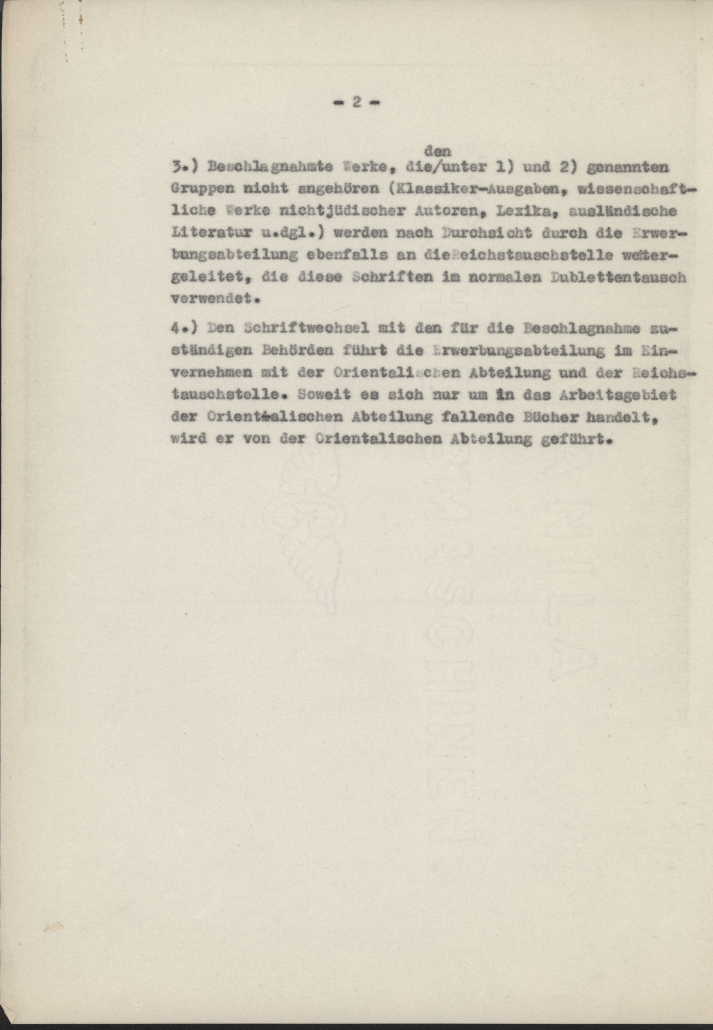

Disputes over confiscated Jewish libraries

The Library of the Jüdisch-Theologisches Seminar Fraenckel’scher Stiftung in Breslau

Two decrees issued by the Reichsminister of Finances on 10 September 1938 and 12 June 1939 declared that the Preußische Staatsbibliothek was the main collecting point for confiscated Jewish and Hebrew literature. However, these decrees never properly came into effect. Especially from 1940 onwards, the Preußische Staatsbibliothek and the (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt were in competition since the latter had been appointed the first place of contact, organising the distribution of confiscated books.

Following the decree of the Reichsfinanzministerium, this letter declares how the Preußische Staatsbibliothek is to proceed with confiscated Jewish and Hebrew literary works. Aktenvermerk zur Behandlung beschlagnahmter jüdischer und hebräischer Literaturerzeugnisse, 24. August 1939. SBB-PK

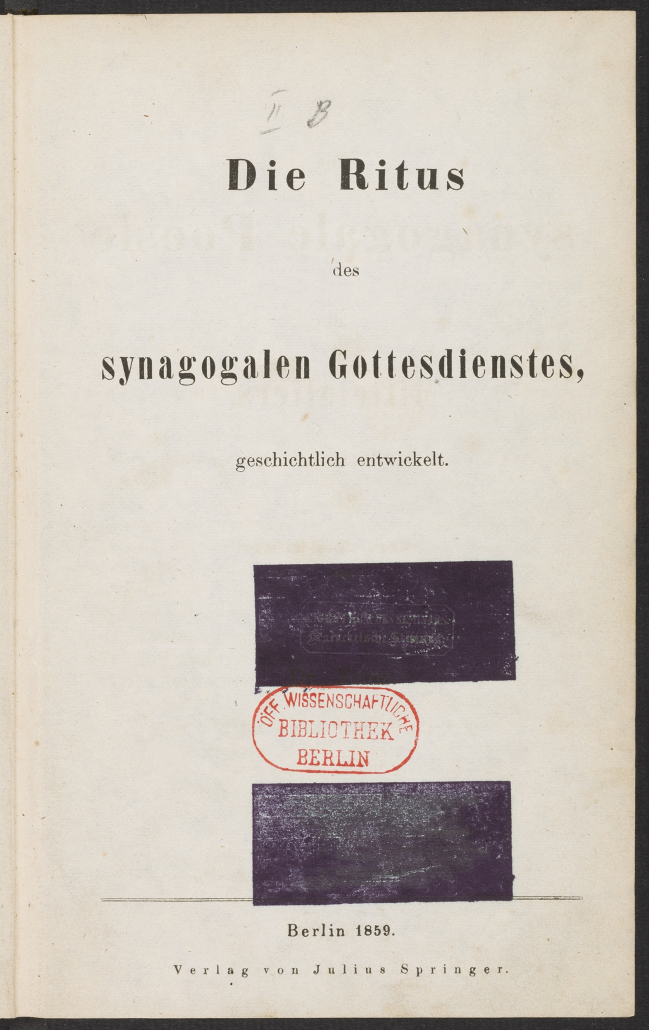

Only a small number of books, which came to the Zentralbibliothek des (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt, were organised and stamped. Often the stamp of the previous owner was blacked out, as can be seen in this book from the Jüdisch-Theologisches Seminar. Leopold Zunz: Die Ritus des synagogalen Gottesdienstes, Berlin 1859. SBB-PK / Hagen Immel

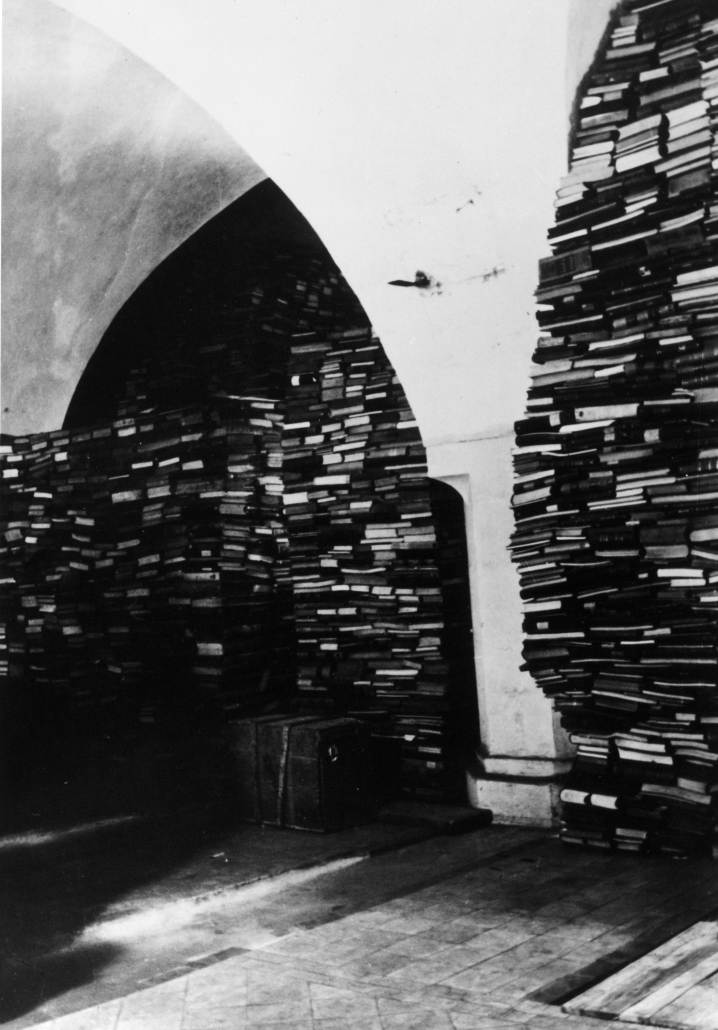

The raid on Jewish libraries in the German Reich, such as the one at the Jüdisch-Theologisches Seminar in Breslau (today Wrocław, Poland), was carried out by the Sicherheitsdienst of the SS. During the November pogroms of 1938, the seminary and library in Breslau were ransacked and destroyed. Any surviving literature was confiscated by the Sicherheitsdienst of the SS to be incorporated into their own central library and was transported to Berlin.

Zentralbibliothek des (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamtes

The (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt was a facility of the SS and created its own library for intelligence work and security service. The library was a main collecting point for confiscated Jewish, Masonic, socialist/Marxist, and other printed works which were unwanted. During the war, some of the books from the Zentralbibliothek were taken out of Berlin or destroyed; the books, which remained in Berlin, were looked at after 1945 by the Bergungsstelle für wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken and returned or distributed to other libraries in Berlin.

The valuable library of the Breslauer Research and learning centre for Jewish Studies was split up again after 1945. Since this seminary and Jewish existence had been severly decimated, it was unclear who the legal successor of the library was. After the library of the (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt was disbanded in 1945, some of its items were distributed to libraries in Berlin; others were given to Jewish communities in Switzerland, Israel, and Mexico via the collecting points of the allies in the US zone of occupation and the trust company Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Inc. Again, other items were taken by Polish government agencies or transported as loot to Moscow. A few copies from the former Jüdisch-Theologische Seminar were sold in antiquarian bookshops. Therefore in the 1990s, Nazi loot was still being added to the collection of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

Like to find out more? Then take a look at ProvenienzWiki! (German only)

Persecuted, robbed, emigrated, or deported – the fate of private individuals and their books

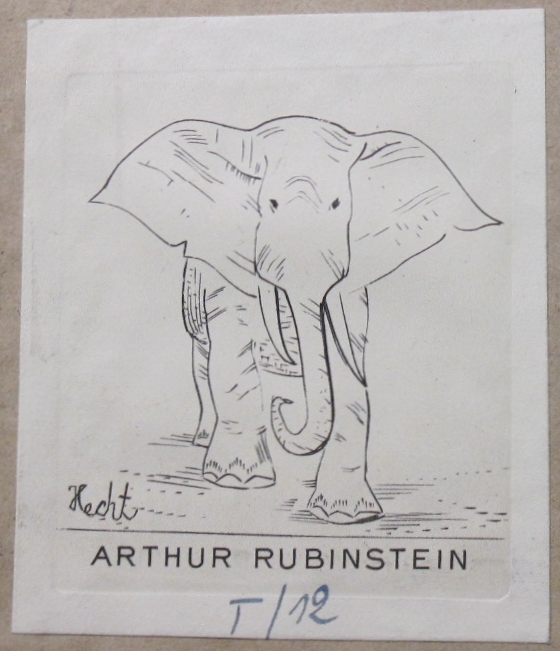

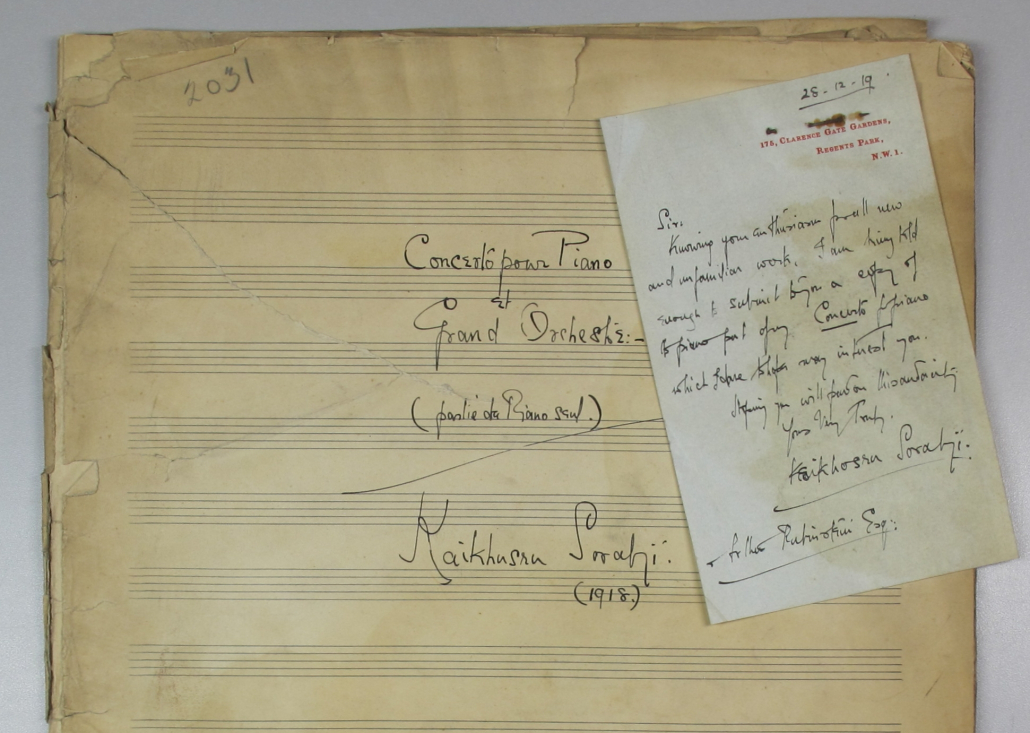

The private library of Artur Rubinstein

The world-famous pianist Artur Rubinstein (1887–1982) owned a valuable private library with numerous music manuscripts in his flat in Paris. In 1939, he emigrated with his family to the United States, whereas his library remained in Paris. After the Germans conquered northern and western France in 1940, Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg was one of the main instigators of large-scale organised raids in occupied territories. Rosenberg and his men confiscated the library’s collections and had them sent to the (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt in Berlin.

Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg

During the Second World War, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg was responsible for the large-scale looting of cultural property in the territories occupied by German troops. Similar to the Sicherheitshauptamt, the confiscated literature was used to establish libraries for the so-called ‘adversary studies’ at the Hohe Schule (Nazi elite school) and at the Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage in Frankfurt am Main.

The splitting up of Rubinstein’s library continued after 1945. A portion of his books were taken from the library of the (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt by the Red Army and transported to Moscow. Anything, which was left behind and regarded as ‘ownerless’, was either handed over to the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, given to other libraries in Berlin for them to restock their collection after the Second World War, or found its way to the Zentralstelle für wissenschaftliche Altbestände. How widely the library’s collection was dispersed remains unclear even today.

Artur Rubinstein, around 1960. bpk

Like to find out more? Then take a look at ProvenienzWiki! (German only)

Restitution

In 2006, the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin returned 71 music manuscripts to Artur Rubinstein’s heirs. Another five books and two music manuscripts were given back in 2019/2020.

While Rubinstein’s books often included an ex-libris, the music manuscripts seldomly did. However, sometimes there were other clues to help identify the rightful owner, like a personal dedication to Artur Rubinstein.

Music manuscript from Artur Rubinstein’s library. SBB-PK / Thomas Rose. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Revisiting the contexts of Nazi loot

Provenance research

Examining the provenance (provenire (lat.) = to come from) of books comes from a long tradition in the research of collections and catalogue descriptions of manuscripts and incunables. In the 1980s, addressing the history and role of libraries under Nazi rule became increasingly more important. In addition, with the introduction of the Washington Principles, scholarly research on the history of ownership and potentially looted library books have gained more recognition. Therefore, studying the provenance of Nazi loot is still a rather new academic discipline. Part of the academic research also focuses on uncovering injustice and determining the legal owners.

For many years now the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, formerly the Preußische Staatsbibliothek, has been working tirelessly on the problem of Nazi-confiscated cultural objects, which are currently in the possession of the Staatsbibliothek. This can be seen in some of the milestones already achieved.

What has been achieved in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin concerning provenance research in libraries

Insights into the work of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Recording Provenance

The entire collection of historical printed works at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin with editions published before 1945 consists of 3 million volumes. In addition, there are special collections, sheet music, maps, and literary estates. The library’s acquisition record for each of these 3 million volumes must be examined in order to uncover items acquired between 1933 and 1945 or later. Any questionable items are subsequently checked. Clues to indicate looted and confiscated works can be found in acquisition records and accession books of the library or in the book itself.

The search for looted books can be rather challenging since many collections were destroyed or as was common library practice any additional copies of the same book were disposed of. Valuable cultural property was transported out of Berlin during the aerial bombings in the Second World War. After the war, book depots were plundered, and items went missing. As of 1945 some depots were on Polish soil. Library collections continued to be dispersed after 1945 as many books, whose origins were not clear, were often redistributed. Due to these distributions, we often only discover parts of collections and books today, even though they may have arrived at the Preußische Staatsbibliothek complete and intact.

The research results of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin regarding solved and unsolved cases are available in the library’s online catalogue. The history of how the book was acquired and restituted to its rightful owner is also documented there.

During the war, collections from the Preußische Staatsbibliothek were taken to estates like the Landgrafenschloss in Marburg an der Lahn. Aufnahme von 1947/48. bpk

Give it a try!

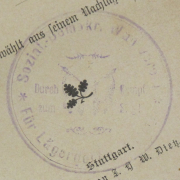

Can you decipher the provenance markings?

Stamps, ex-libris, or personal dedications in books are clues, which help identify the previous owner. However, deciphering these markings can prove to be very challenging and is not always possible.

Solution

Sozial.-Demokr. Wahlverein

Für Lägerdorf

Durch Kampf zum Sieg!

Further information

Smaller libraries of local party offices as well as labour associations were confiscated in large quantities during the Nazi regime.

Solution

Aus meiner Bücherei

Hedwig Hesse

Behrmann

Mai 1918

Nr.

Further information

Hedwig Hesse was a German Jew, who was deported to Riga in 1942 and murdered. Her books were confiscated.

Solution

Gr. L. Loge D. Fr. M. V. Deutschl.

[Grosse Landesloge der Freimaurer von Deutschland]

Berlin

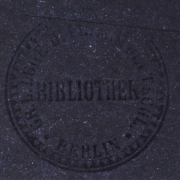

Bibliothek

Further information

The blacked-out stamp indicates that this volume was taken from a Masonic lodge and handed over to the (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt.

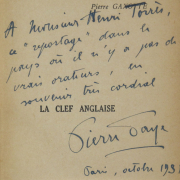

Solution

À Monsieur Henri Torrès

ce “reportage” dans le pays

où il n’y a pas de

vrais orateurs, en

souvenir très cordial

Pierre Daye

Paris, octobre 1931

Further information

The French lawyer Henry Torrès had Jewish roots and emigrated to the United States in 1940. The books from his library probably came to the Preußische Staatsbibliothek through various routes.

Solution

Israelitischer Knaben-Verein Stettin

Further information

As this volume belonged to a Jewish association, it most probably fell victim to Nazi raids. So far, there are no further clues as to which library it came from.

Returning Nazi-confiscated cultural property to the rightful owners

Restitution

The first restitutions of Nazi-confiscated cultural property were made soon after the war in 1945. A significant amount of Nazi loot was found at the many storage locations throughout the German Reich. The (Reichs-)Sicherheitshauptamt and Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, leading instigators of Nazi loot left behind large depots full of confiscated property. Therefore, the allies tried to start returning the looted property to the rightful owners. The Offenbach Archive Depot for books and documents in the US zone was the central collecting point. Between 1945 and 1949 the Offenbach Depot returned 3 million books and ritual objects. In 1945/46, the Bergungsstelle für wissenschaftliche Bibliotheken in Berlin took on the responsibility of examining collections that had been left behind and organising returns.

However, not all books and documents could be identified, allocated, and returned. The search for Jewish owners was particularly difficult because the Nazis had completely destroyed the Jewish way of life. In addition, there were many books without any clues as to the previous owners. These were regarded as ‘ownerless’ and therefore distributed. Returning books from east to west and vice versa was even more difficult during the Cold War. As a result, there is still Nazi loot left in library collections today.

On 23 June 2016 the Director General of the SBB, Barbara Schneider-Kempf, returned 384 volumes, which had previously belonged to the lodge library and were identified by the SBB as Nazi loot, to the head of the Johannisloge Teutonia zur Weisheit in Potsdam. SBB-PK / Hagen Immel

The Staatsbibliothek marks returned copies with a distinctive stamp. SBB-PK / Hagen Immel

The likelihood of finding rightful owners 70 years after the end of the war has become increasingly slim. In most cases, it is only possible to contact heirs and in some cases no rightful heirs are to be found. Many books contain no clues about previous owners, and it can only be assumed that they might be Nazi loot. These books are indicated as such in the online catalogue of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

Restitutions of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

In numbers

The huge number of 3 million historical printed works, published before 1945, shows that the Staatsbibliothek will be dealing with the issue of Nazi loot in their collections for a long time to come. This task is especially difficult considering the devastating losses suffered due to the war, those books no longer being in the Staatsbibliothek, and considering that the library was split into two institutions, east and west, from 1946 to 1990. How far the examination of the collections of the Staatsbibliothek has proceeded can be seen in the numbers mentioned above. Information on how many volumes have been either identified as or are suspected of being Nazi-confiscated objects or how many have already been returned, is regularly updated and made available in the online-catalogue of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.